2017

This project was completed in collaboration with Caroline Acheatel and studio critic Tatiana Bilbao.

Urban Design

¡AGUA ADELANTE!

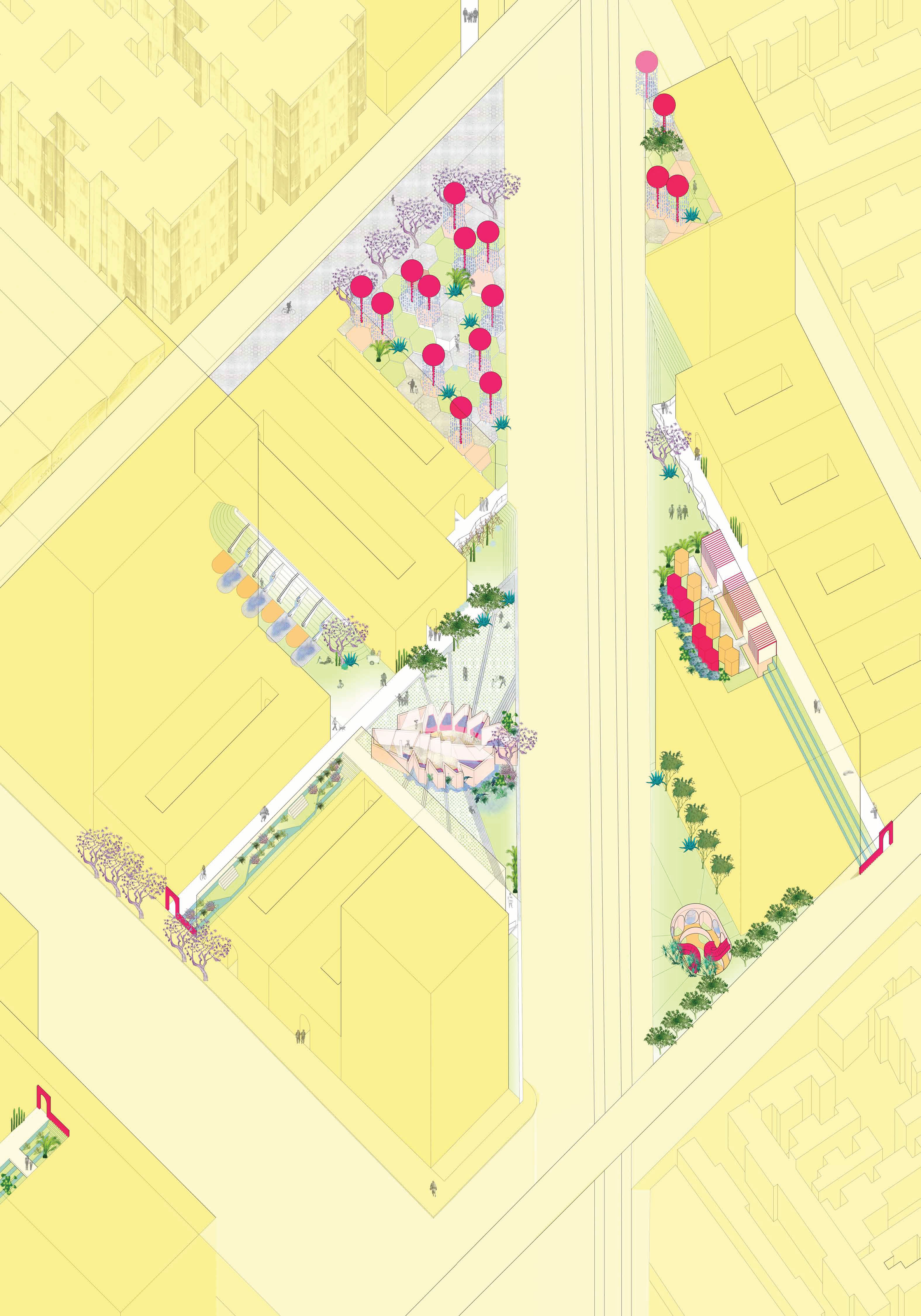

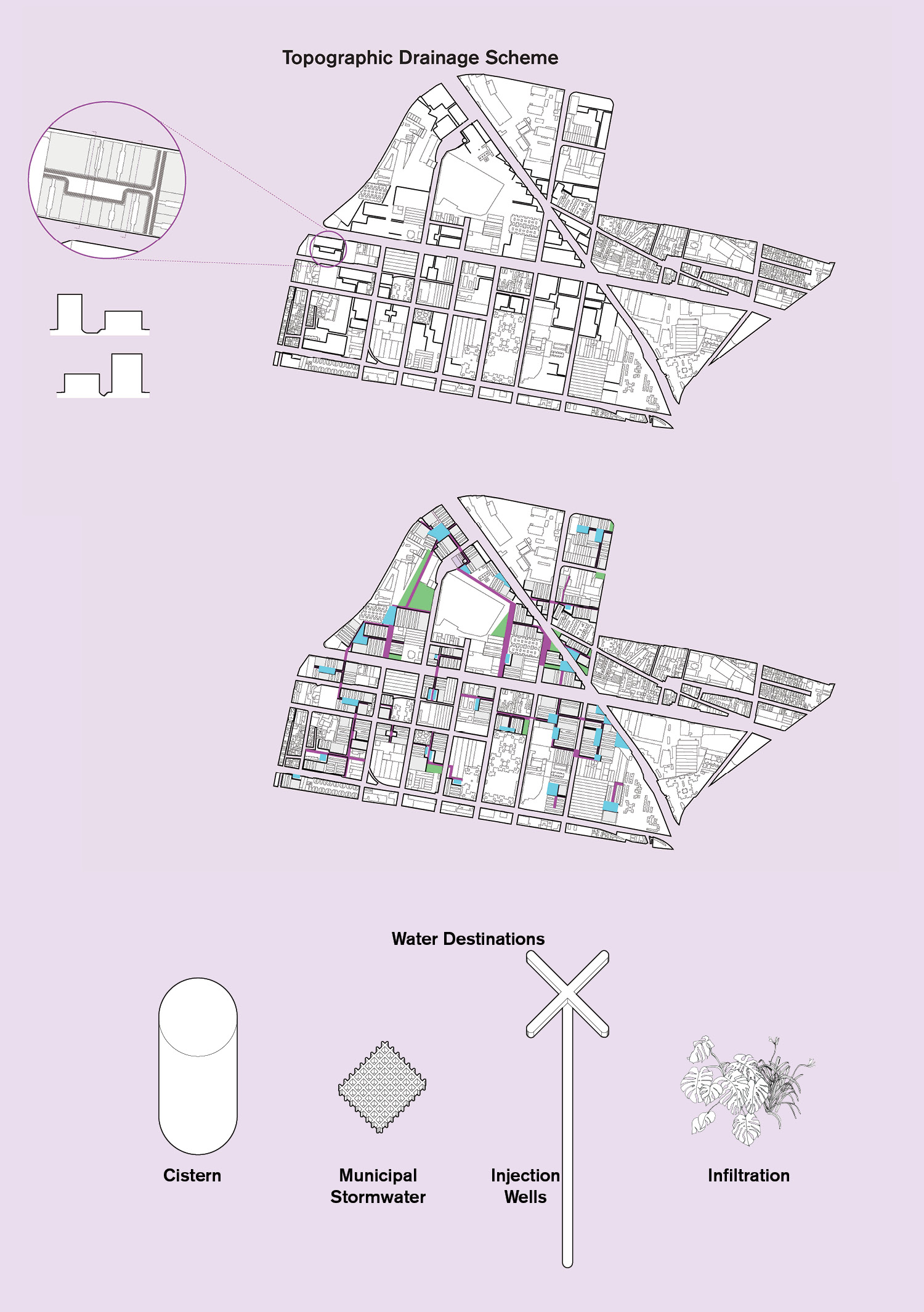

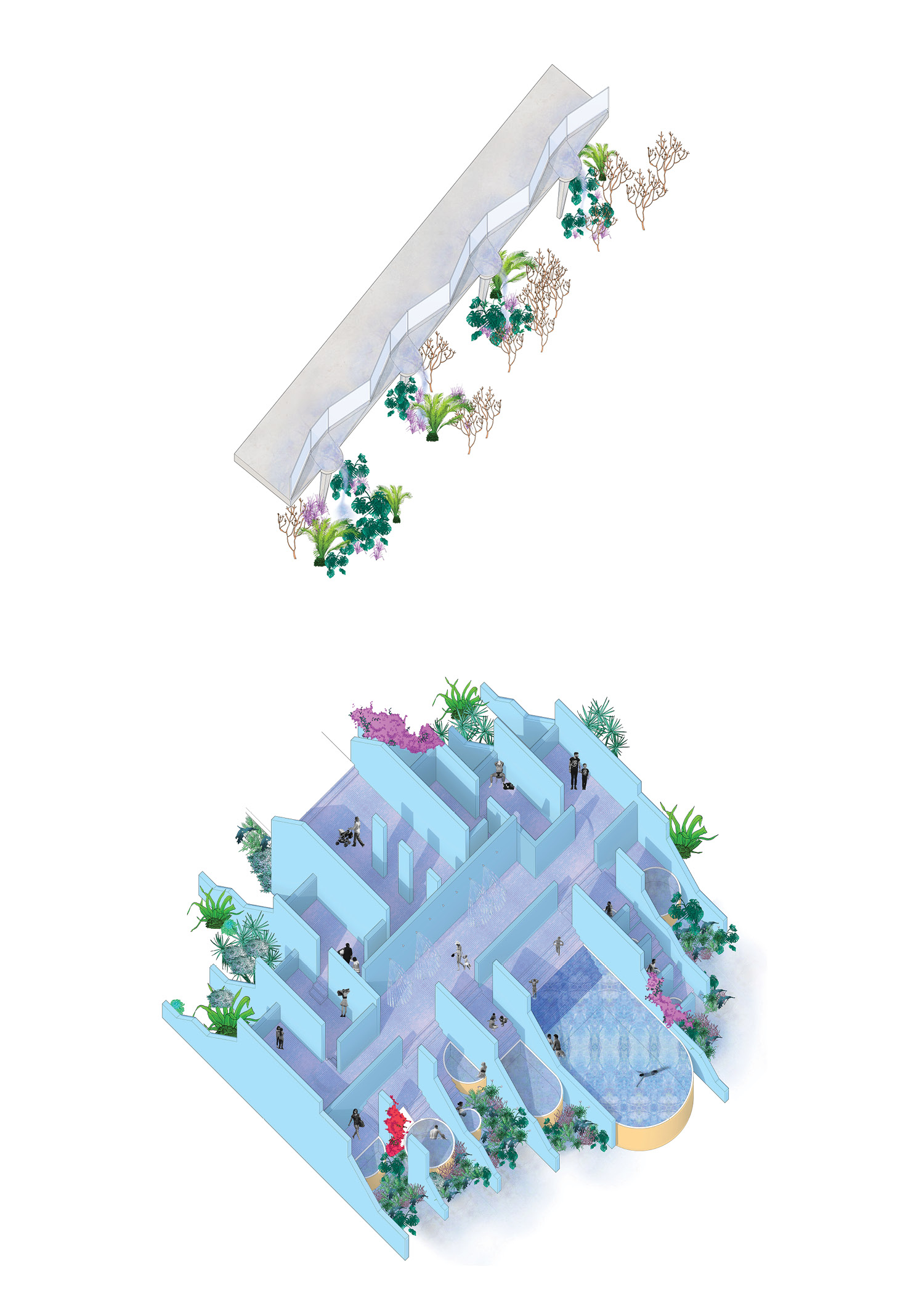

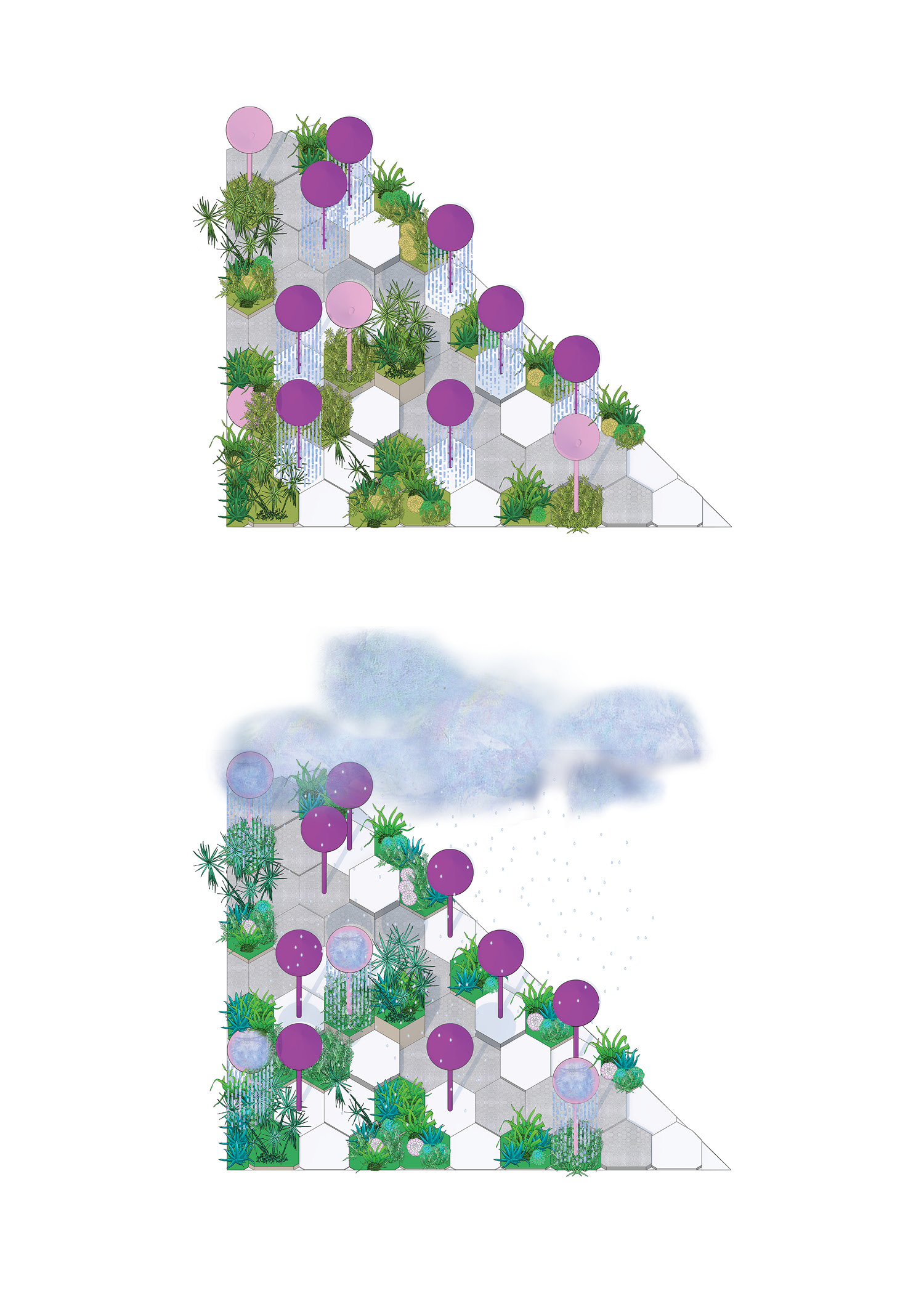

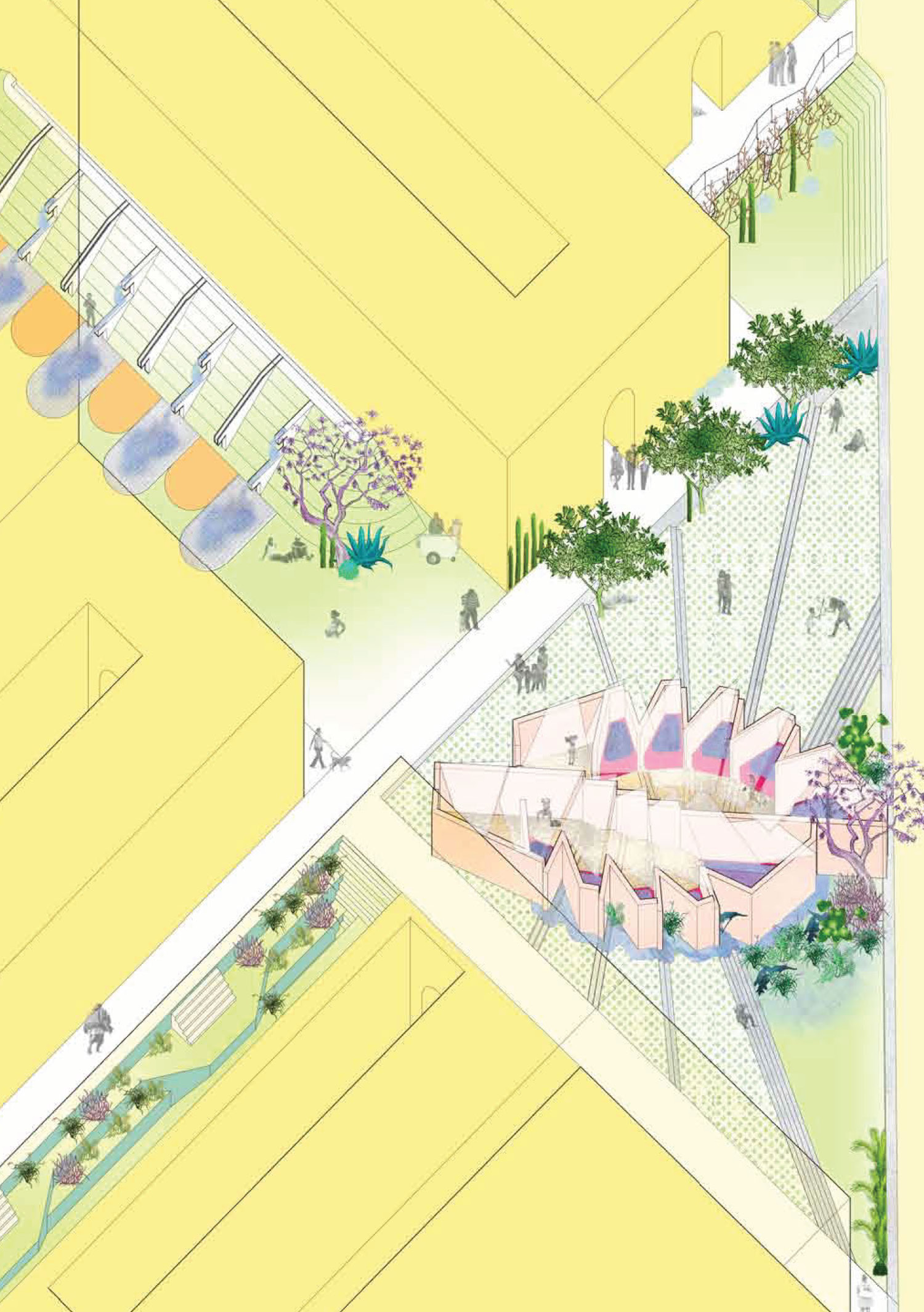

This project imagines how equitable water practices can drive the design of a generous public realm in Mexico City, where rapid development and economic segregation has caused uneved access to environmental resources, such as water. This project asks how Mexico City’s seasonal water scarcity and flash floods, made worse by climate change, might be mitigated through shared space. Can public space bridge income divides between communities in a highly segregated city marked by gates, security cameras, and body guards? Can climate adaptation be recreation?

In this climate future, new housing developments are built to tie into a comprehensive stormwater plan. Within the system, basins work together with technical elements to divert and absorb stormwater, and at the same time, form a network of public spaces used for pedestrian circulation and recreation. Public spaces, including community bathhouses and parks, are designed with interactive water features so that users learn about water use, reuse, conservation, and filtration while occupying them. Basins, parks, residential typologies, pedestrian paths, and bathhouses come together to develop a landscape that addresses climate change and water management through leisure activity.

2017

Paprika! Vol. 3 No. 14, Co-edited with Tess McNamara and Katherine Stege, Graphic Design by Erik Freer.

Read the full issue here.

Paprika! Vol. 3 No. 14, Co-edited with Tess McNamara and Katherine Stege, Graphic Design by Erik Freer.

Read the full issue here.

Editing

![]()

![]()

![]()

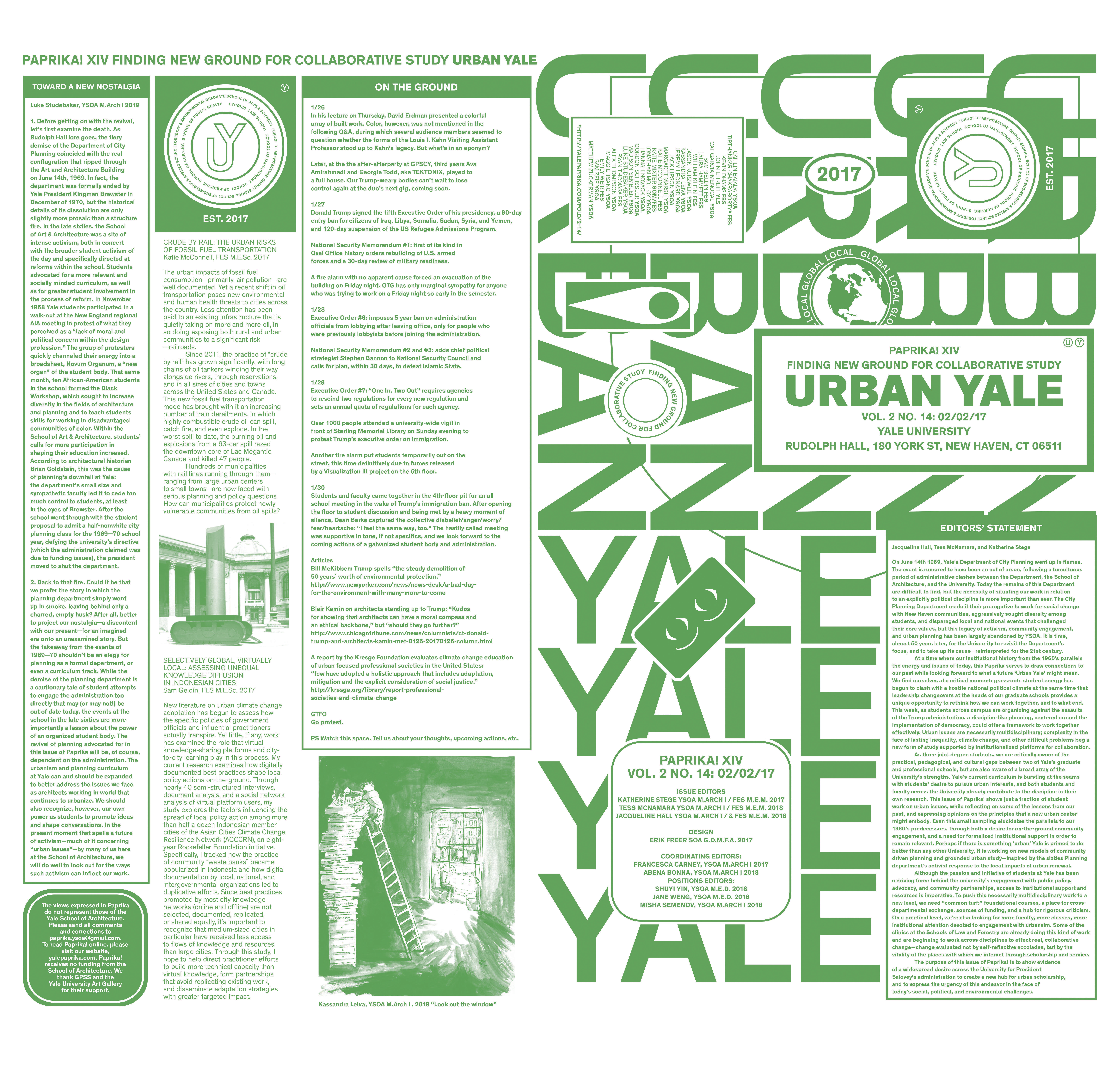

URBAN YALE

This issue of Paprika! advocates for the establishment of a new interdisciplinary hub for urban studies at Yale. Inside are excerpts of student work on urban issues, showing just a small selection of all the urban work currently being done at Yale. We also reflect on some of the lessons from Yale’s past urban planning department, and propose principles that a new urban center at Yale might embody.

This sample of current work shows parallels to our predecessors in the 1960s planning deparment. Then, as now, there was desire for on-the-ground community engagement in New Haven, and the belief that the school needed to formally include urbanism in its curriculum in order to stay relevant as an institution. Today, many in the School of Architecture believe that students are being deprived an essential set of tools because the institution is not committed to placing architecture in the larger context of planning, and politics.

This issue of Paprika! advocates for the establishment of a new interdisciplinary hub for urban studies at Yale. Inside are excerpts of student work on urban issues, showing just a small selection of all the urban work currently being done at Yale. We also reflect on some of the lessons from Yale’s past urban planning department, and propose principles that a new urban center at Yale might embody.

This sample of current work shows parallels to our predecessors in the 1960s planning deparment. Then, as now, there was desire for on-the-ground community engagement in New Haven, and the belief that the school needed to formally include urbanism in its curriculum in order to stay relevant as an institution. Today, many in the School of Architecture believe that students are being deprived an essential set of tools because the institution is not committed to placing architecture in the larger context of planning, and politics.

2018

This project was completed with studio critics Pier Vittorio Aureli and Emily Abruzzo.

This project was completed with studio critics Pier Vittorio Aureli and Emily Abruzzo.

Urban Design

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

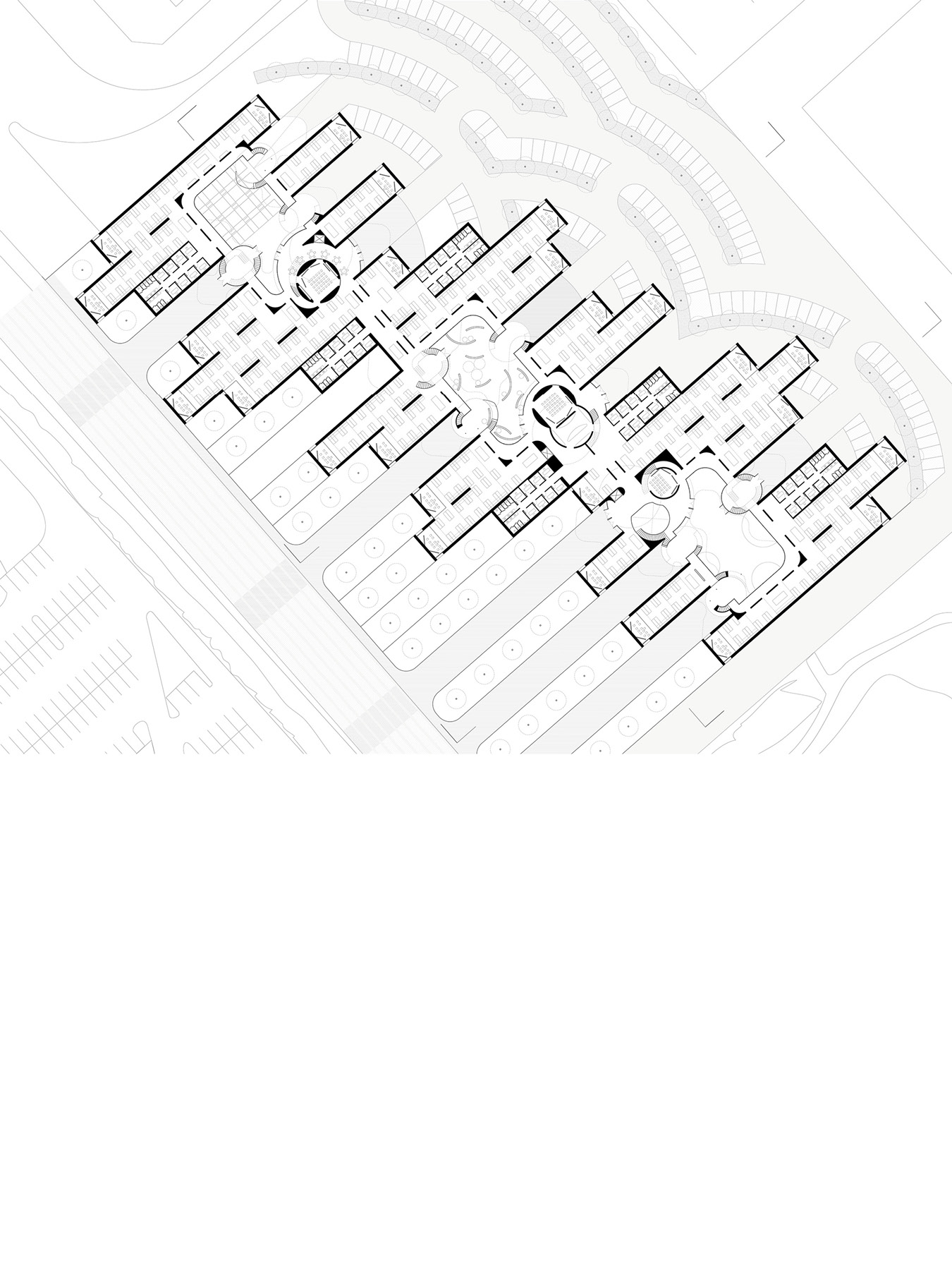

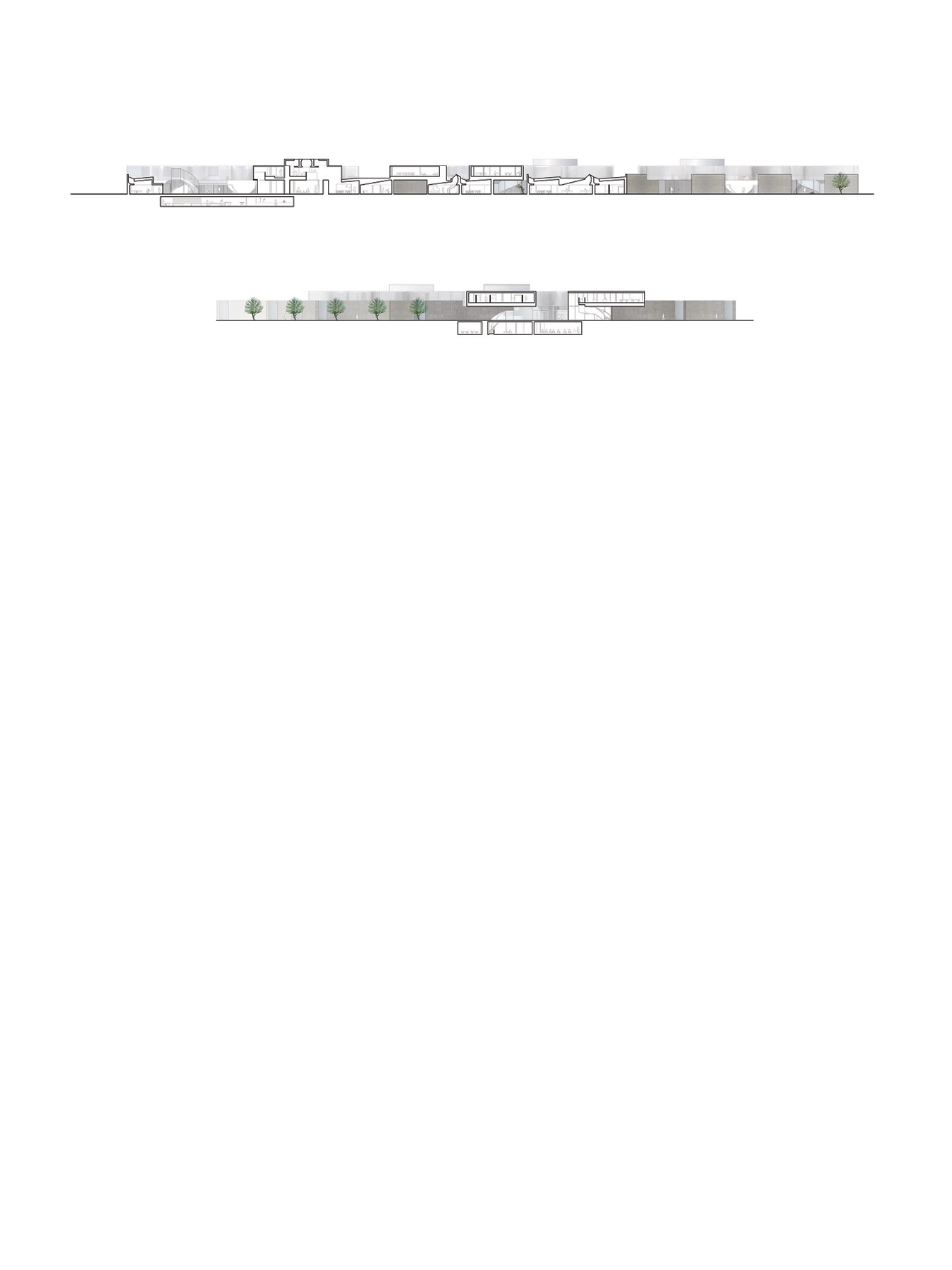

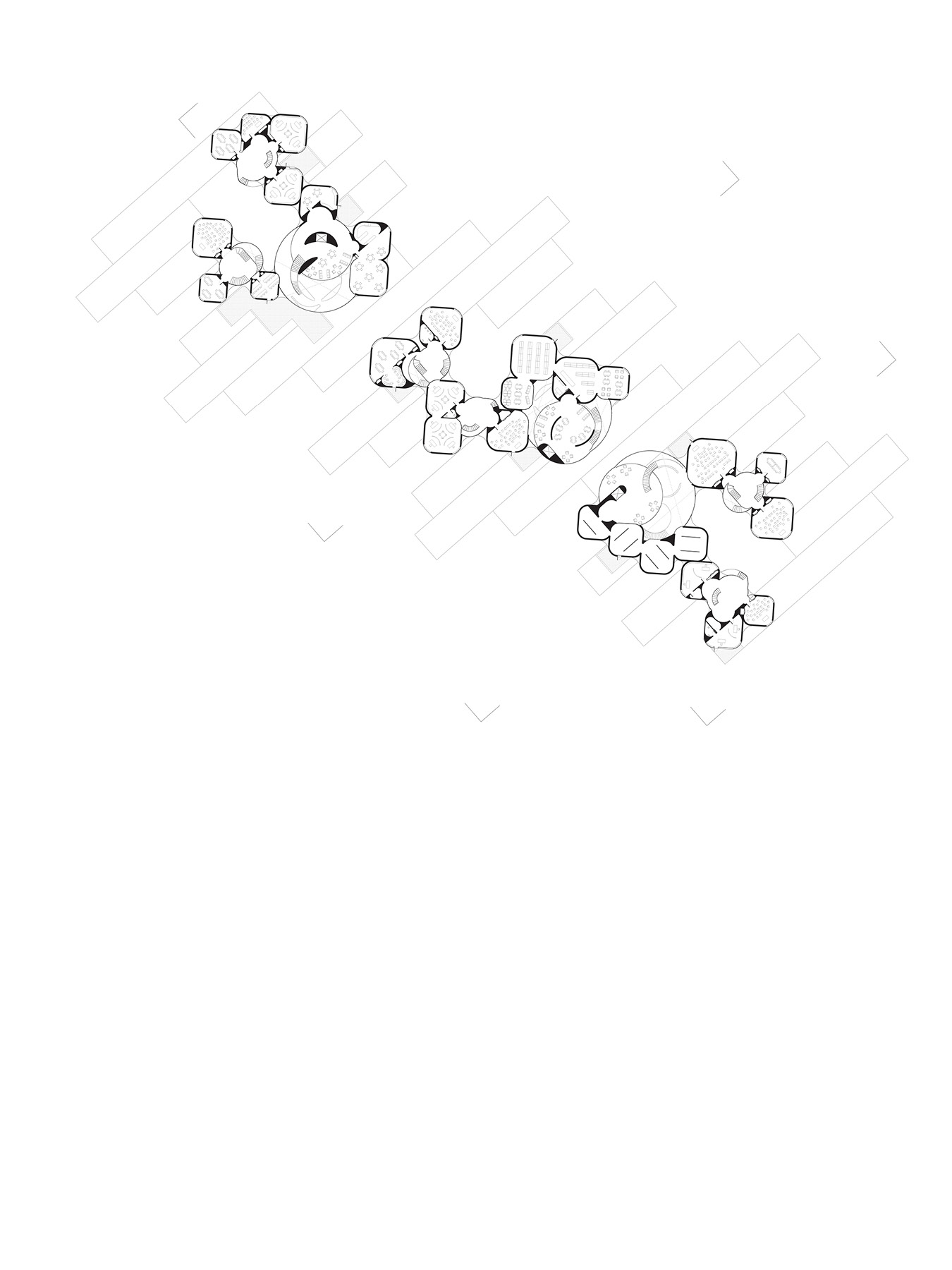

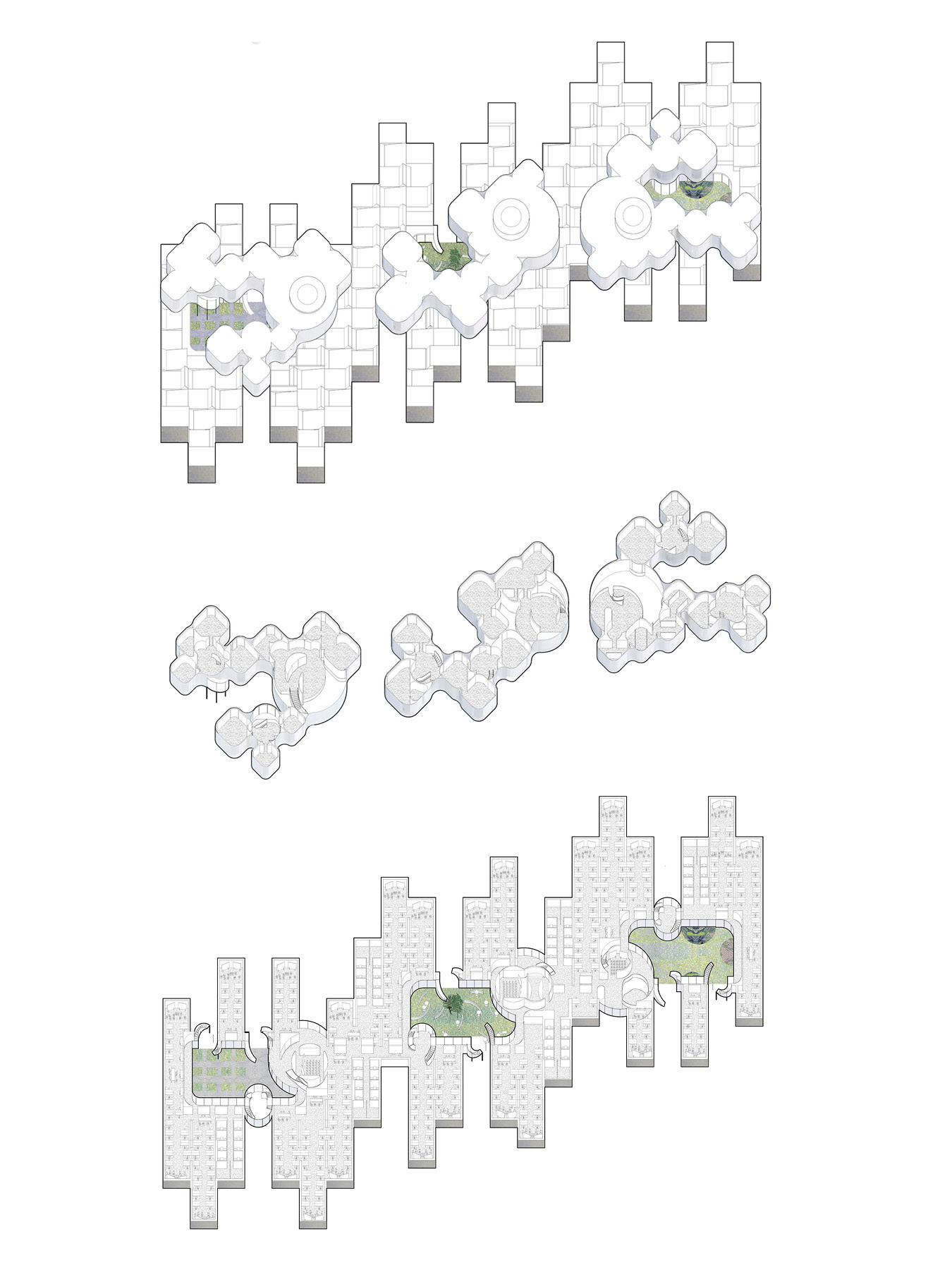

TOR BELLA MONACA

Tor Bella Monaca was the built on the periphery of Rome the 1980s as the city’s last social housing project. Now, poorly maintained and stigmatized, the neighborhood is socially and physically isolated from much of the city. Paradoxically, Tor Bella Monaca also has many social services that are otherwise scarce in Rome’s more affluent suburbs. It’s home to a vibrant theater, several schools, churches, shopping areas, and sits at the edge of beautiful Roman countryside.

Within the neighborhood, the landscape is in a state of neglect. In a recent survey, residents reported feeling satisfied with their apartments but disappointed with the quality of public spaces. Their feelings are no surprise. The ground between Tor Bella Monaca’s apartment buildings is an undifferentiated sprawl of parking lots and oversized roads.

Starting from this context, the project imagines a new ground for Tor Bella Monaca. In my proposal, the land beneath clusters of buildings is relinquished by the Italian government, who has already abandoned it, and given over to cooperatives of residents. The ground is then transformed into a series of outdoor rooms that can be managed and appropriated by the community over time. The project suggests configurations of rooms and planting strategies to offer a diversity of ecological and social conditions across the site.

Tor Bella Monaca was the built on the periphery of Rome the 1980s as the city’s last social housing project. Now, poorly maintained and stigmatized, the neighborhood is socially and physically isolated from much of the city. Paradoxically, Tor Bella Monaca also has many social services that are otherwise scarce in Rome’s more affluent suburbs. It’s home to a vibrant theater, several schools, churches, shopping areas, and sits at the edge of beautiful Roman countryside.

Within the neighborhood, the landscape is in a state of neglect. In a recent survey, residents reported feeling satisfied with their apartments but disappointed with the quality of public spaces. Their feelings are no surprise. The ground between Tor Bella Monaca’s apartment buildings is an undifferentiated sprawl of parking lots and oversized roads.

Starting from this context, the project imagines a new ground for Tor Bella Monaca. In my proposal, the land beneath clusters of buildings is relinquished by the Italian government, who has already abandoned it, and given over to cooperatives of residents. The ground is then transformed into a series of outdoor rooms that can be managed and appropriated by the community over time. The project suggests configurations of rooms and planting strategies to offer a diversity of ecological and social conditions across the site.

2019-present

Art

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

These pieces are distillations of ideas about landscape done in a slower, clumsier, medium. I also wanted a medium that would help me to think more clearly about composition and to pull colors I’m drawn to into strange and exciting relationships.

Many of these compositions come from my interest in spaces that create a gradient of intimacy, or, in Beatriz Colomina’s words, “the interesection of claustrophobia and agoraphobia.” Though actually I’d rather call it the intersection of claustrophilia and agoraphilia!

It’s possible to create so many of these kinds of liminal spaces by recombining very simple forms.

2015

Completed with studio instructor Emily Abruzzo.

Completed with studio instructor Emily Abruzzo.

Architecture

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

NESTING

How can a building foster community for a large and potentially alienating design school of 750 students? Sited across from parking lots and next to a chemical plant and office park, this project turns inward, focusing community life around three courtyards. The courtyards are designed in relation to the ancillary programs on the floors above and below: shop, library, gallery, cafe, and lecture hall. All studio space is equally accessible from the ground floor of the building. These work spaces are tied together with a series of group meeting and circulation spaces of varying character. The landscape is also designed to provide many unique pathways into the school.

The courtyards create distinct and intimate neighborhoods. Everyone enters the school through their respective courtyard, encouraging familiarity and chance encounters among students, faculty and staff. This, combined with intentionally small studio spaces, nests many intimate communities within the larger school.

How can a building foster community for a large and potentially alienating design school of 750 students? Sited across from parking lots and next to a chemical plant and office park, this project turns inward, focusing community life around three courtyards. The courtyards are designed in relation to the ancillary programs on the floors above and below: shop, library, gallery, cafe, and lecture hall. All studio space is equally accessible from the ground floor of the building. These work spaces are tied together with a series of group meeting and circulation spaces of varying character. The landscape is also designed to provide many unique pathways into the school.

The courtyards create distinct and intimate neighborhoods. Everyone enters the school through their respective courtyard, encouraging familiarity and chance encounters among students, faculty and staff. This, combined with intentionally small studio spaces, nests many intimate communities within the larger school.

2015-2018

I organized the Equality in Design lecture series and organized other school advocacy between the fall of 2015 and the spring of 2018. Graphic design by Caroline Potter, Erik Freer, Maggie Tsang, Nat Pyper, Ingrid Chen, Rosen Tomov, Simone Cutri, and Micah Barrett.

I organized the Equality in Design lecture series and organized other school advocacy between the fall of 2015 and the spring of 2018. Graphic design by Caroline Potter, Erik Freer, Maggie Tsang, Nat Pyper, Ingrid Chen, Rosen Tomov, Simone Cutri, and Micah Barrett.

Organizing

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

EQUALITY IN DESIGN

Equality in Design is a coalition of students at the Yale School of Architecture committed to expanding access to the profession of architecture. Our programming engages architecture’s social and political context and implications.

The group holds discussions and lectures with students and faculty, and group members organize a variety of other advocacy campaigns and events at the school. These range from lunch discussions with local activists and planners, to a special edition of the school newspaper published in response to the Shitty Architecture Men List.

We also want to engage with related disciplines to better understand architecture’s place in fostering a more ethical and just world. We believe that our studies at YSoA can and should expand the purview of architectural studies to include the prevailing social, cultural, and ethical questions of our time.

Equality in Design is a coalition of students at the Yale School of Architecture committed to expanding access to the profession of architecture. Our programming engages architecture’s social and political context and implications.

The group holds discussions and lectures with students and faculty, and group members organize a variety of other advocacy campaigns and events at the school. These range from lunch discussions with local activists and planners, to a special edition of the school newspaper published in response to the Shitty Architecture Men List.

We also want to engage with related disciplines to better understand architecture’s place in fostering a more ethical and just world. We believe that our studies at YSoA can and should expand the purview of architectural studies to include the prevailing social, cultural, and ethical questions of our time.

2016

This project was completed in collaboration with Laura Meade and with studio critic Bimal Mendis.

This project was completed in collaboration with Laura Meade and with studio critic Bimal Mendis.

Urban Design

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

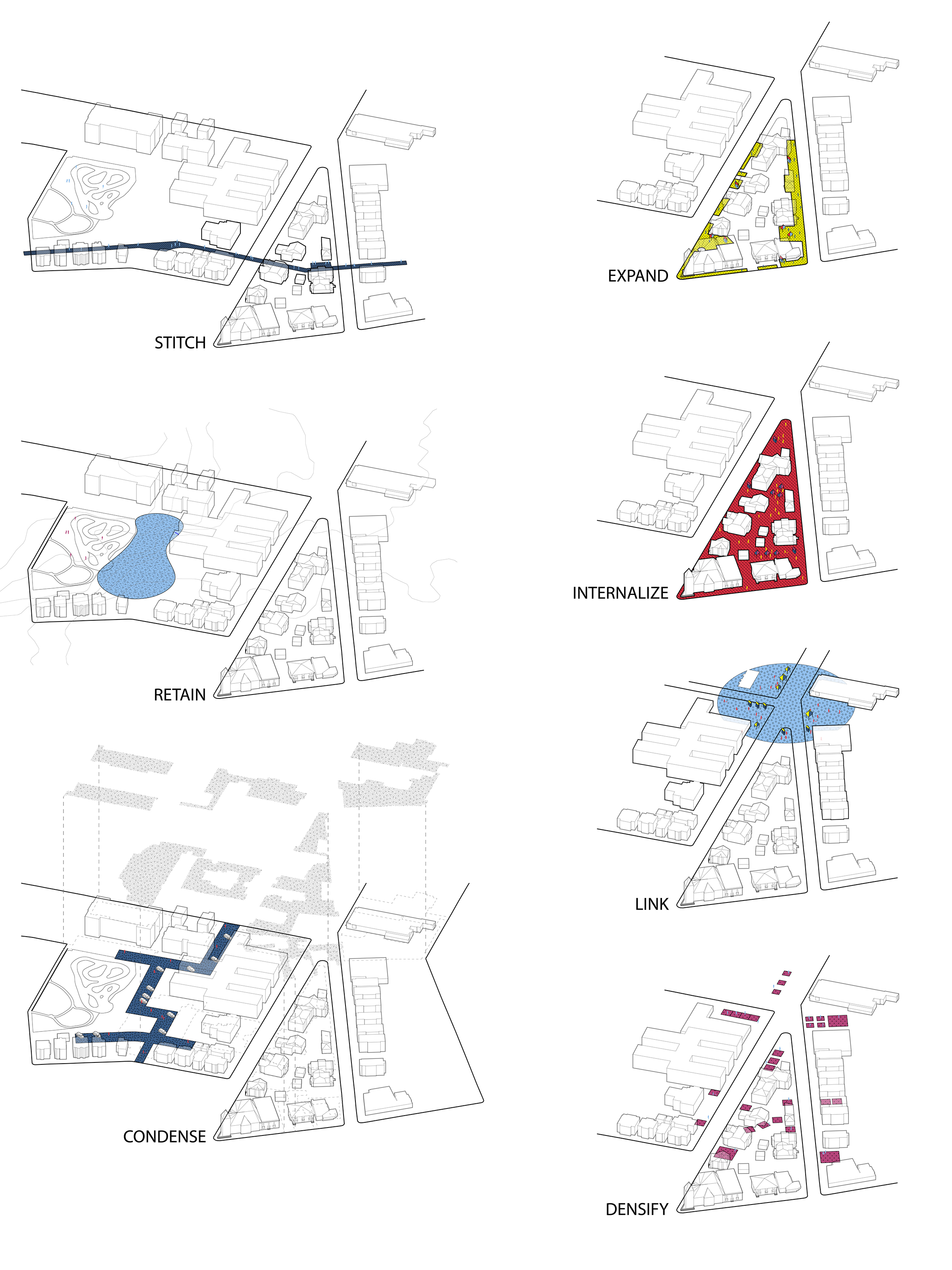

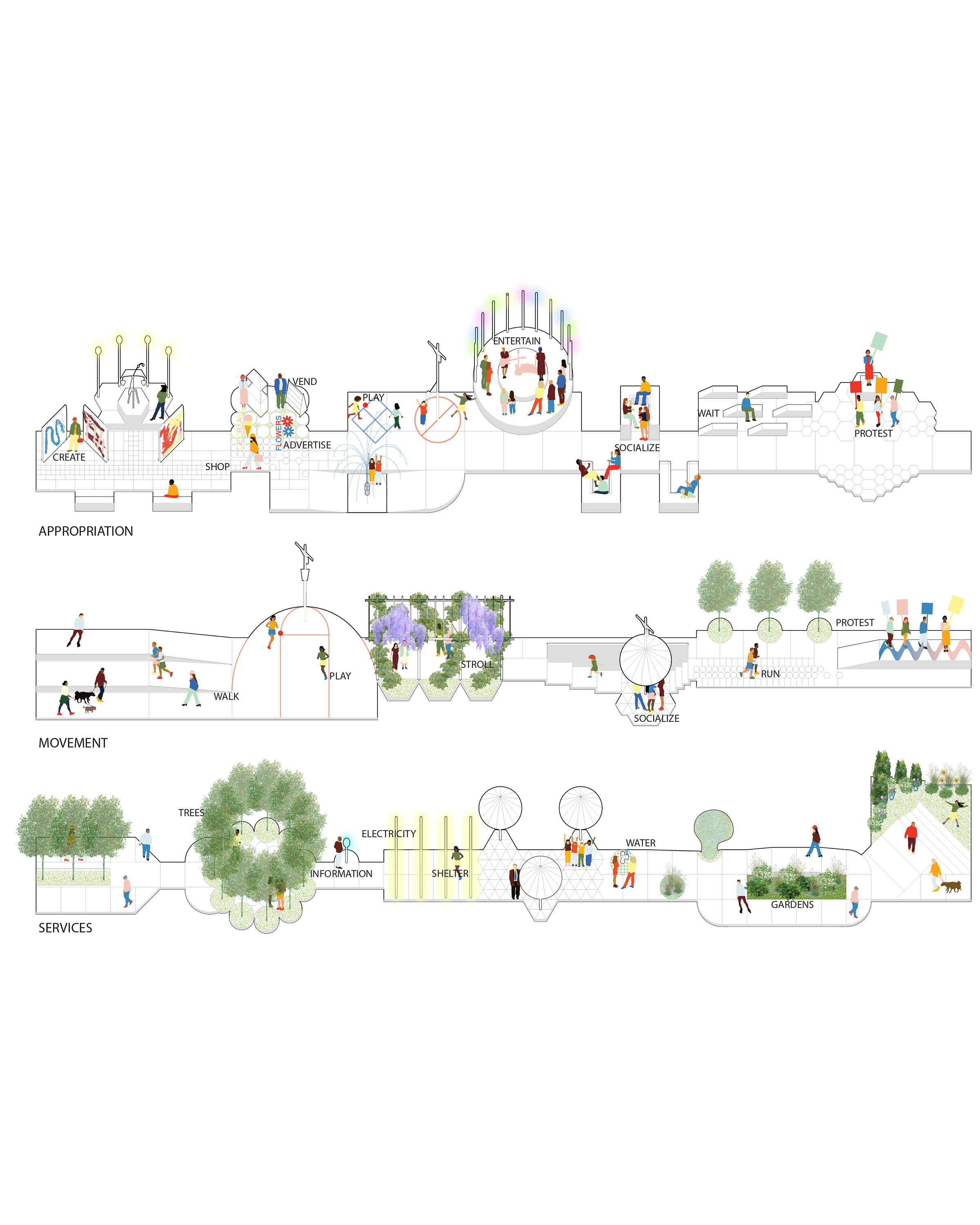

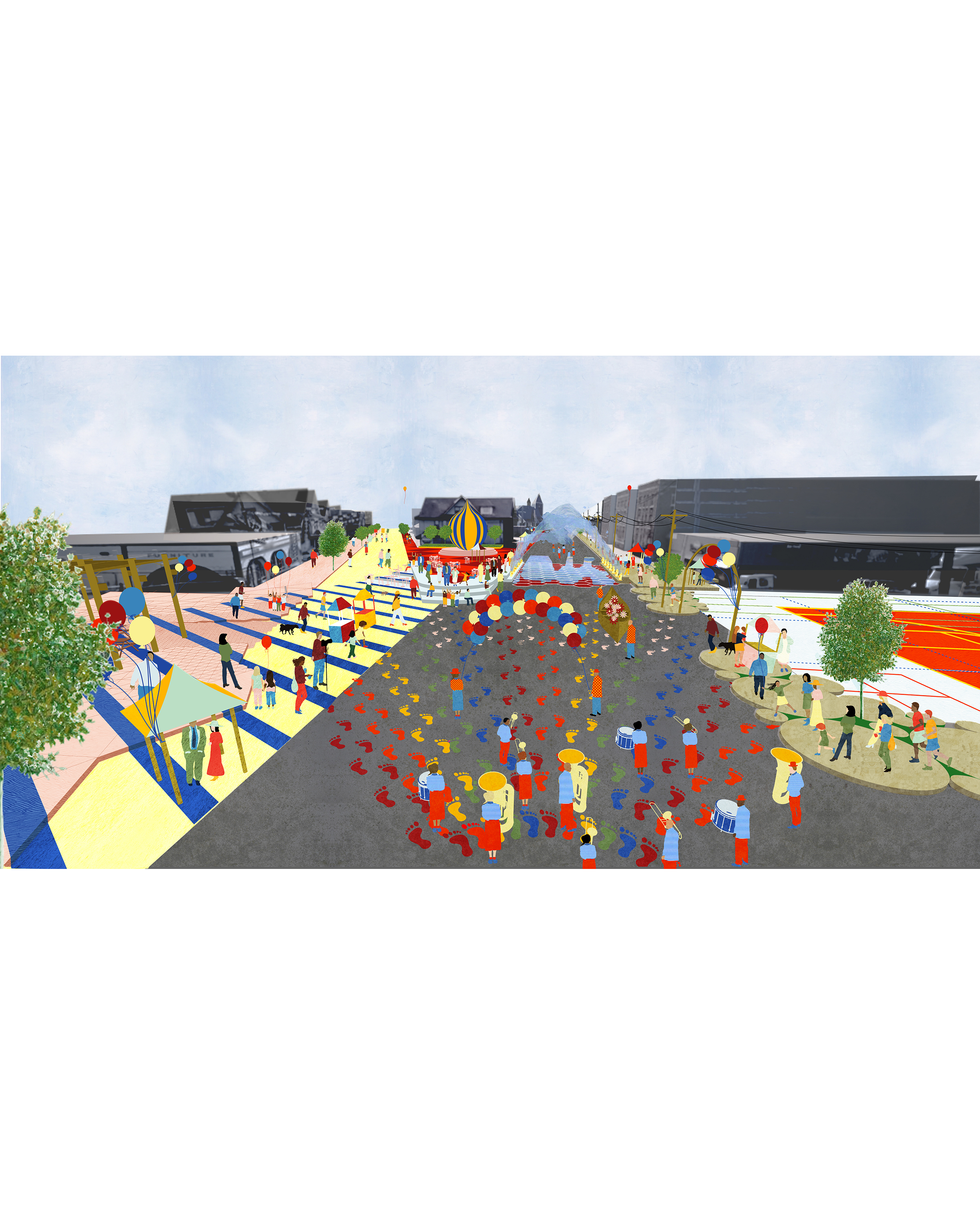

SIDEWALKING

Sidewalks are the city’s most public realm. Despite the ubiquity and homogenous design of sidewalks, they are the connective tissue on which the most specific neighborhood conditions are played out – Bridgeport’s cultural identity lives and evolves within its system. Social relationships are given a surface area in the public realm on the sidewalk.

The sidewalk is the infrastructure that allows people to physically relate to the city. This project expands the potential of existing sidewalks and exploits how subtle changes can profoundly impact the different facets of a city’s skin. Only by rearranging existing sidewalk features, the project seeks to communicate a more democratic array of uses to more people.

We’ve used this site in the city of Bridgeport, Connecticut, to identify types of existing public activity that might communicate more effectively through their adjacency to the new sidewalk. “Sidewalking” is the act of cataloging useful components of the sidewalk and subtly manipulating their form to hack their results and increase their function.

Sidewalks are the city’s most public realm. Despite the ubiquity and homogenous design of sidewalks, they are the connective tissue on which the most specific neighborhood conditions are played out – Bridgeport’s cultural identity lives and evolves within its system. Social relationships are given a surface area in the public realm on the sidewalk.

The sidewalk is the infrastructure that allows people to physically relate to the city. This project expands the potential of existing sidewalks and exploits how subtle changes can profoundly impact the different facets of a city’s skin. Only by rearranging existing sidewalk features, the project seeks to communicate a more democratic array of uses to more people.

We’ve used this site in the city of Bridgeport, Connecticut, to identify types of existing public activity that might communicate more effectively through their adjacency to the new sidewalk. “Sidewalking” is the act of cataloging useful components of the sidewalk and subtly manipulating their form to hack their results and increase their function.

2017

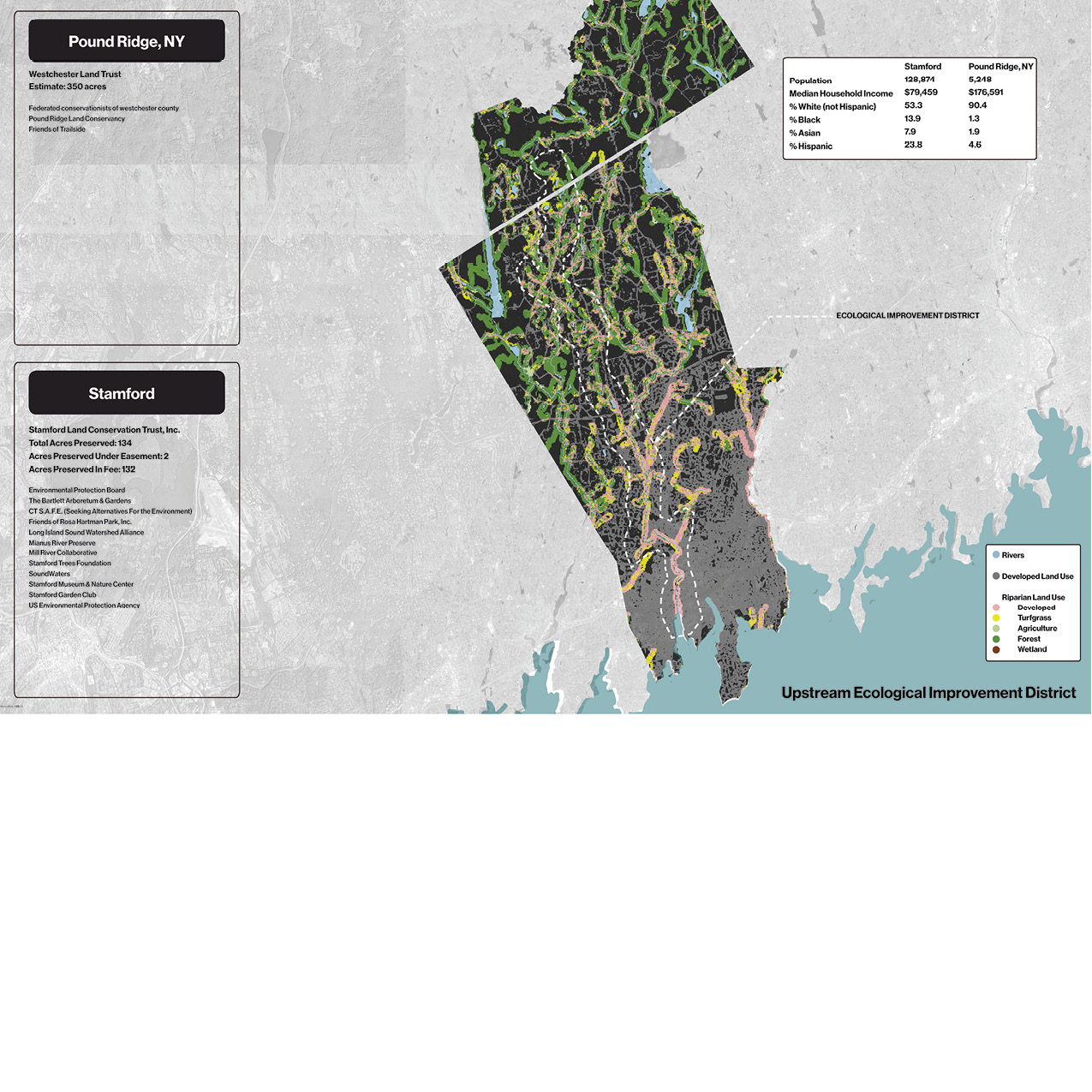

This project was completed in collaboration with Justin Lai, Emma Greenbaum, and Eli Ward in Alexander Felson’s Ecological Urban Design course.

This project was completed in collaboration with Justin Lai, Emma Greenbaum, and Eli Ward in Alexander Felson’s Ecological Urban Design course.

Ecological Planning

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

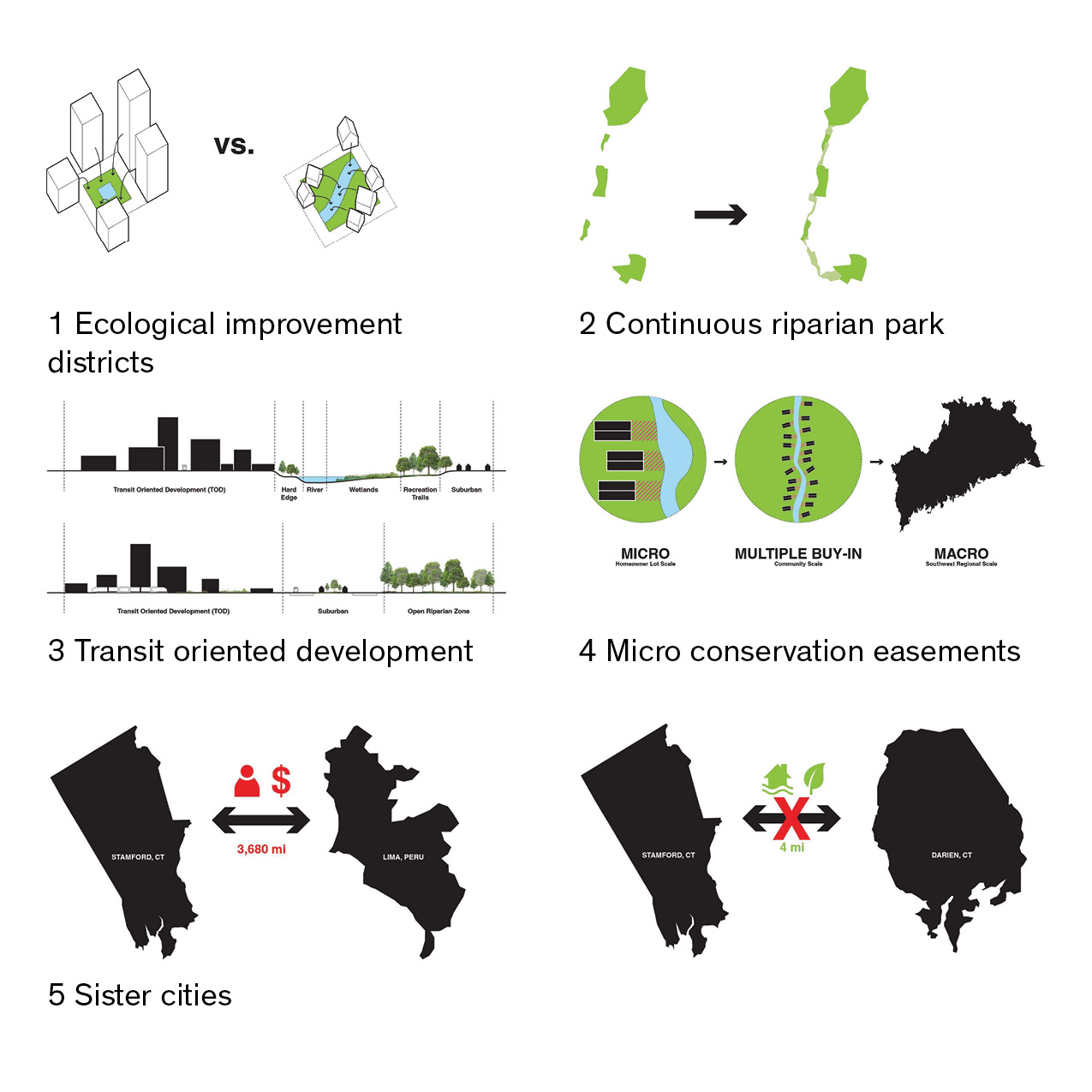

CT SW COAST

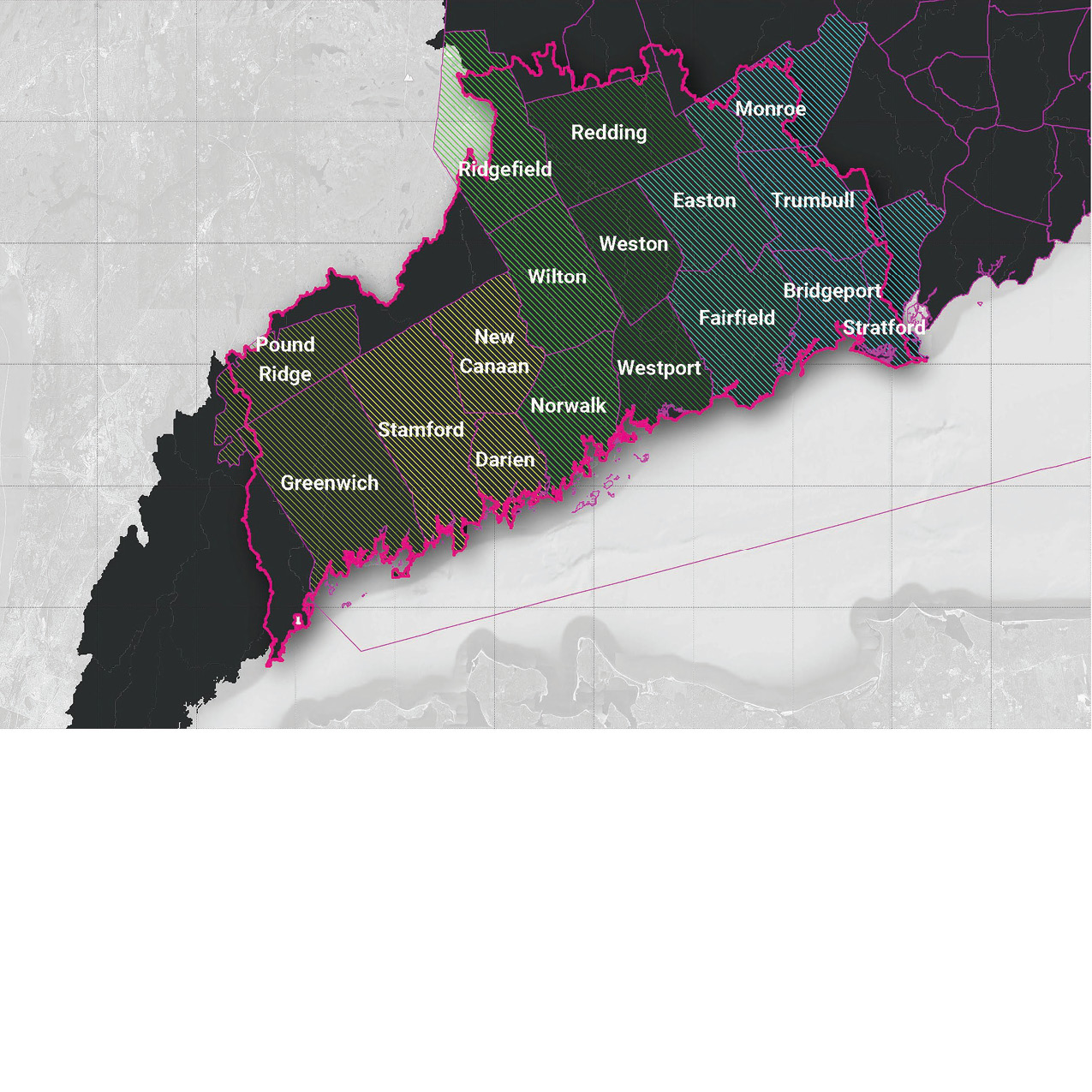

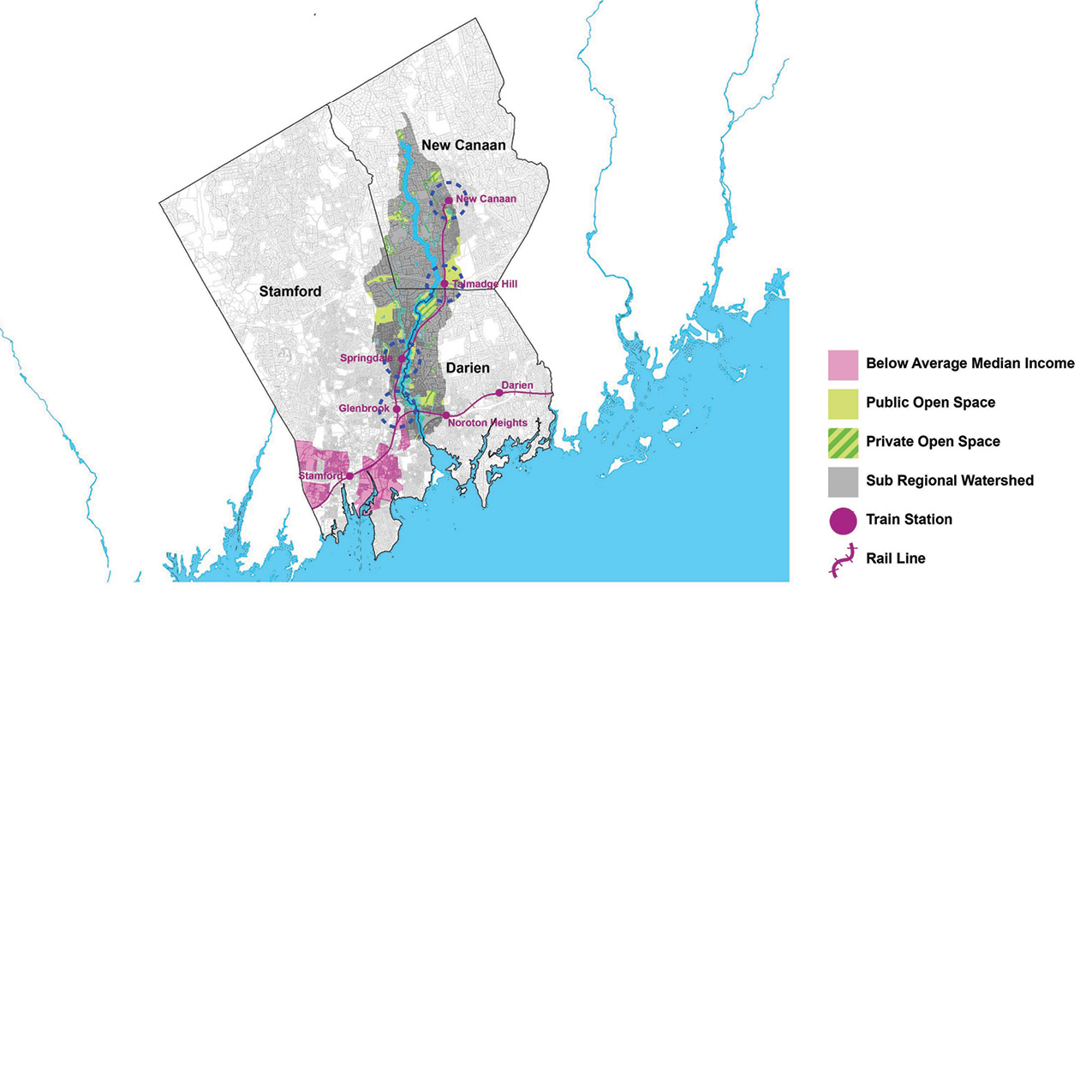

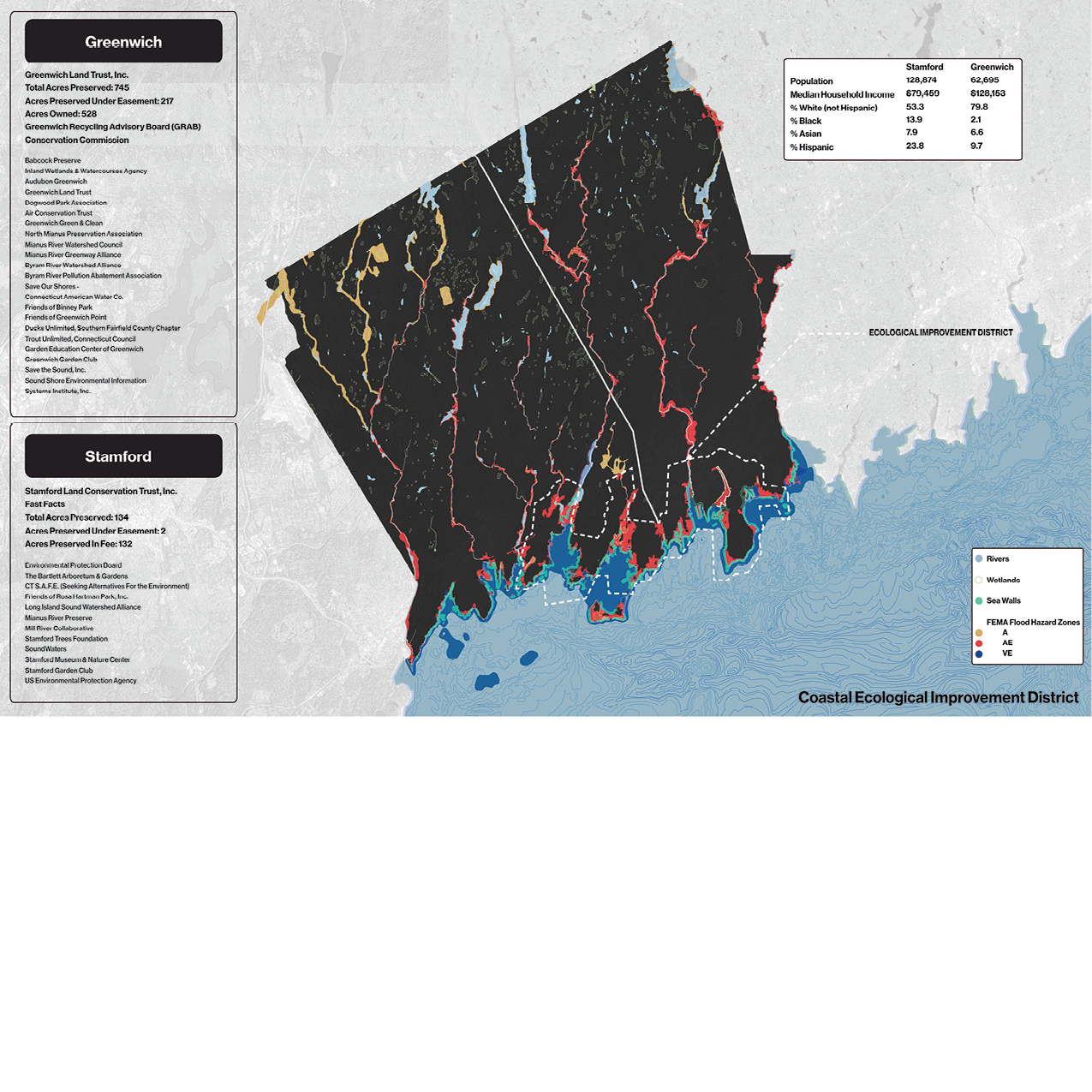

Located in the Southwest Coast watershed of Connecticut, this project poses cross-municipal collaboration on ecological vitality based on shared ecological risk.

The towns of the Southwest Coast are characterized by extreme economic inequality set in a landscape of shared coastal and inland flooding risk, as well as significant hypoxia problems in Long Island Sound. We used the Noroton River subregional basin as a case study because it runs south from the town of New Canaan to form the border between Stamford and Darian. It also has relatively low water quality compared to other rivers in the Southwest Coast.

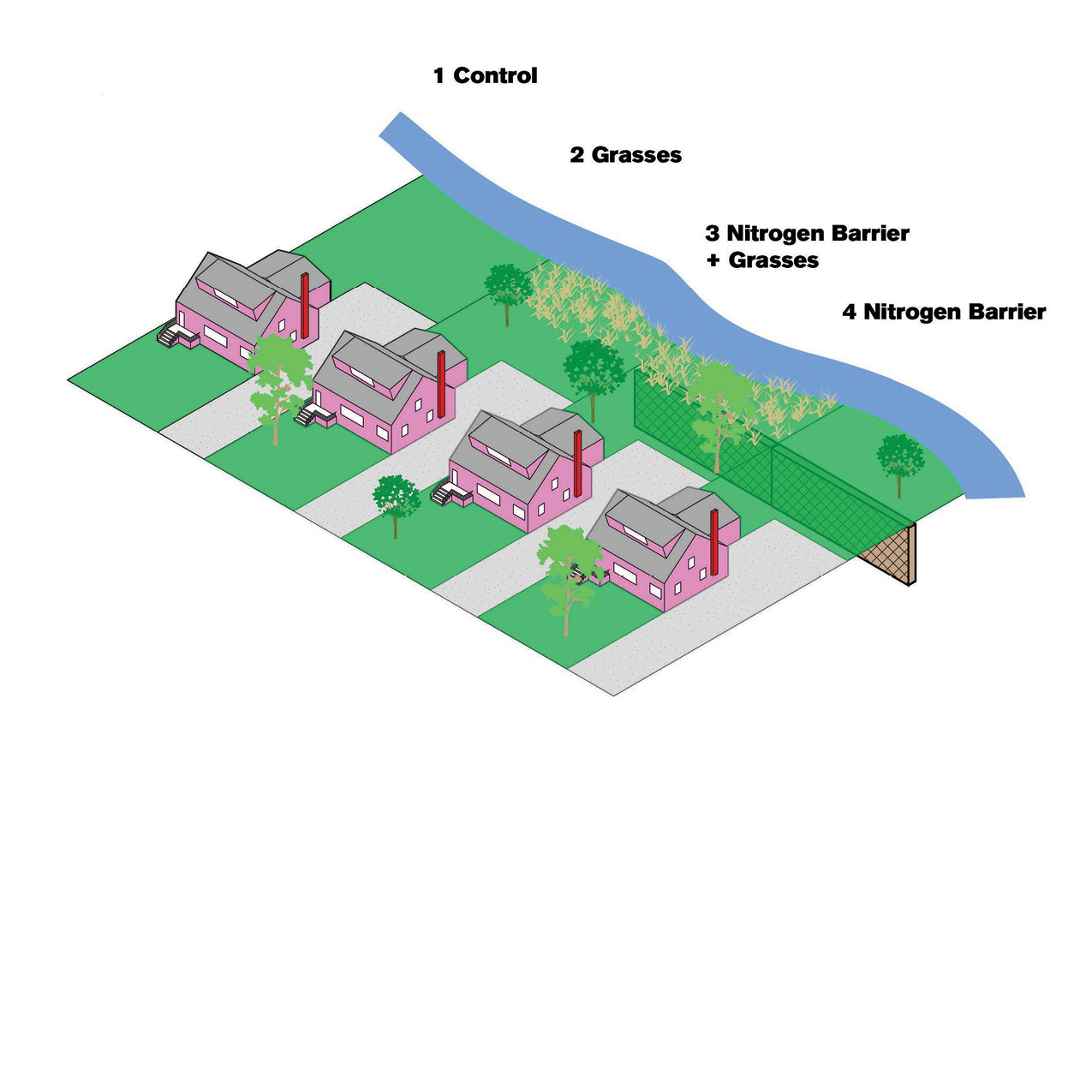

The proposal attempts to approach socio-economic disparities by establishing sister-city relationships in “Ecological Improvement Districts,” with various planning mechanisms in which towns work together to improve riparian health, establish low-income housing in transit oriented development, reduce vulnerability in flood zones, improve water quality, and implement designed experiments to test ecological land-use

strategies.

Located in the Southwest Coast watershed of Connecticut, this project poses cross-municipal collaboration on ecological vitality based on shared ecological risk.

The towns of the Southwest Coast are characterized by extreme economic inequality set in a landscape of shared coastal and inland flooding risk, as well as significant hypoxia problems in Long Island Sound. We used the Noroton River subregional basin as a case study because it runs south from the town of New Canaan to form the border between Stamford and Darian. It also has relatively low water quality compared to other rivers in the Southwest Coast.

The proposal attempts to approach socio-economic disparities by establishing sister-city relationships in “Ecological Improvement Districts,” with various planning mechanisms in which towns work together to improve riparian health, establish low-income housing in transit oriented development, reduce vulnerability in flood zones, improve water quality, and implement designed experiments to test ecological land-use

strategies.

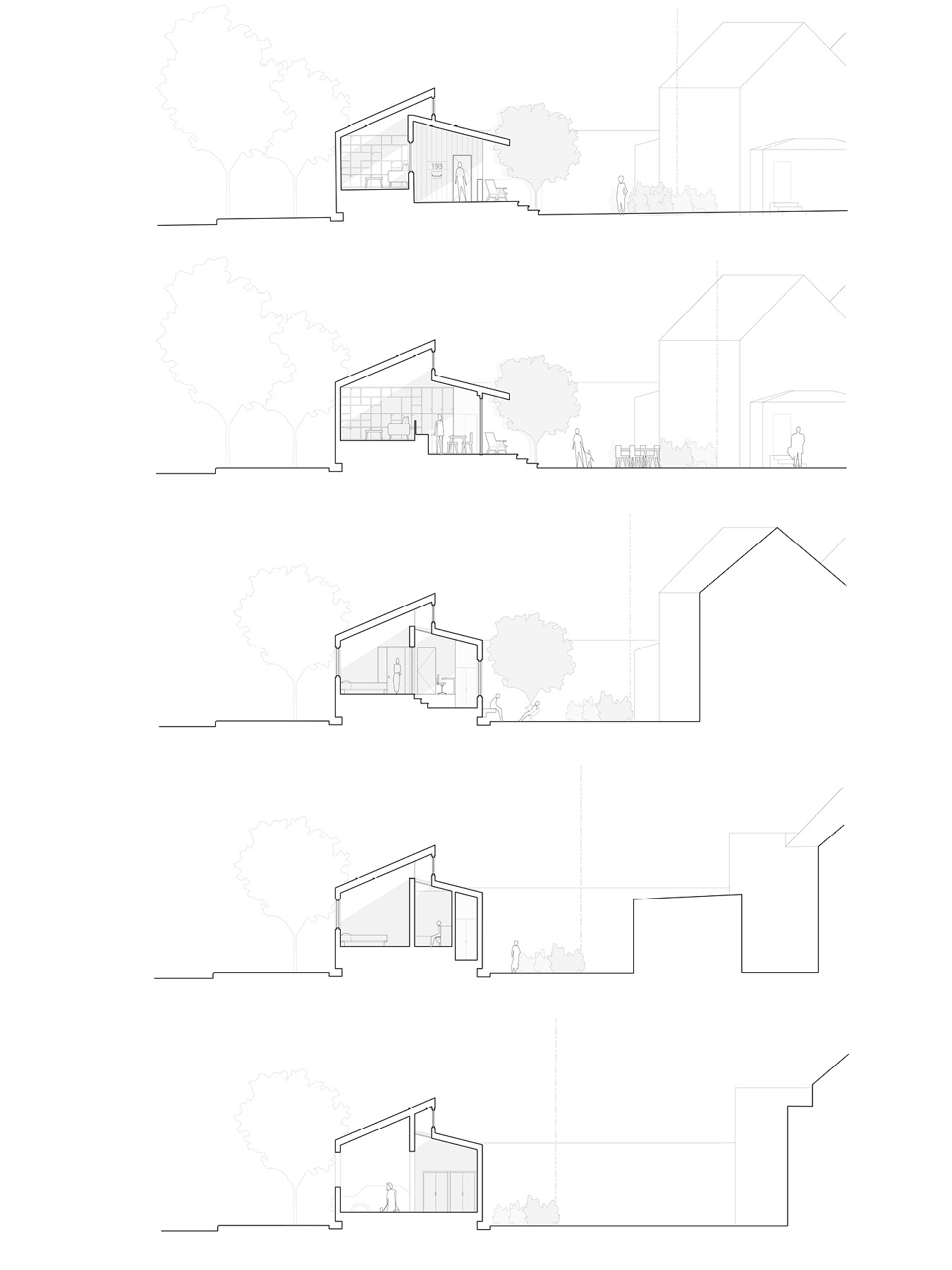

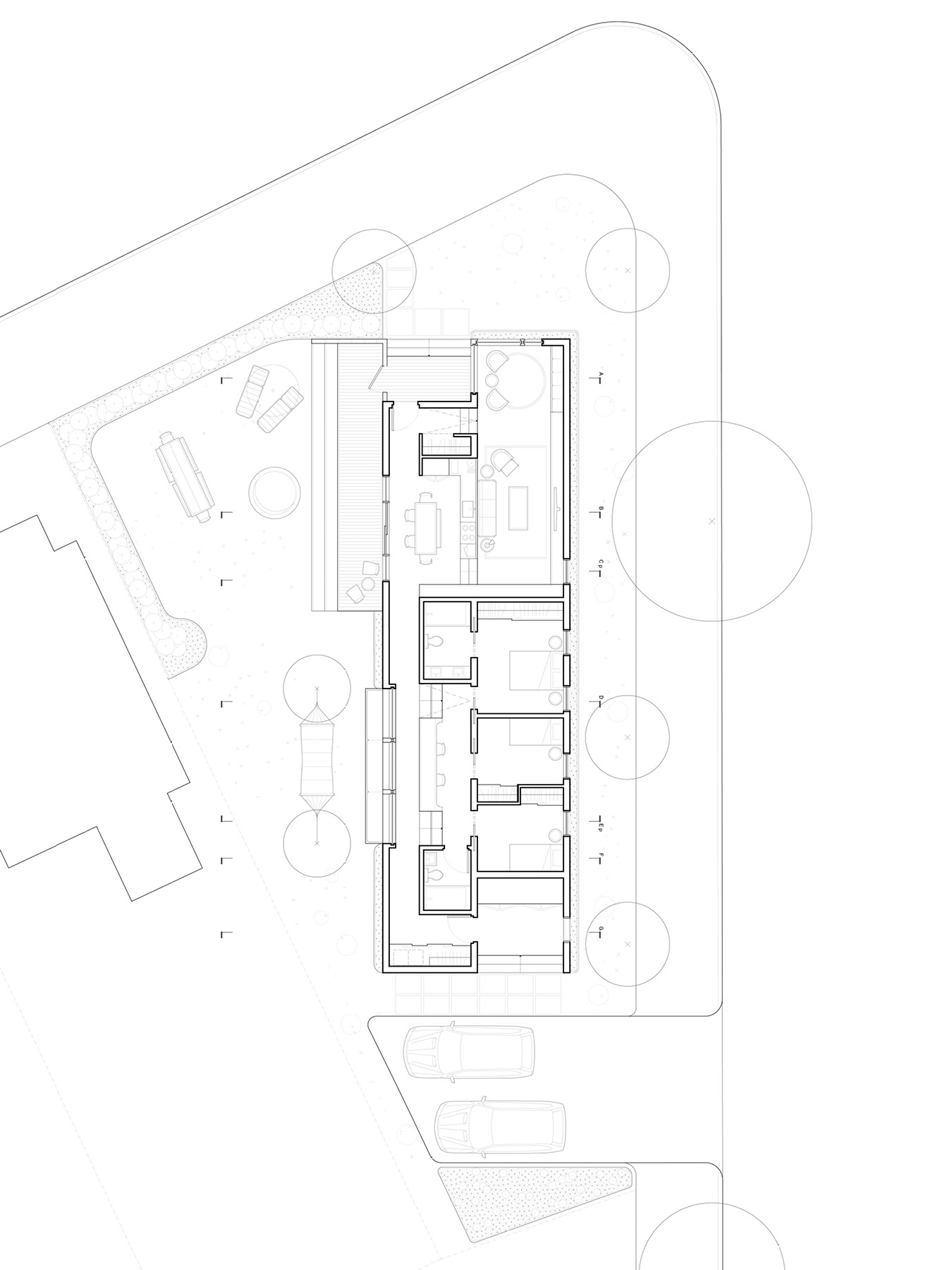

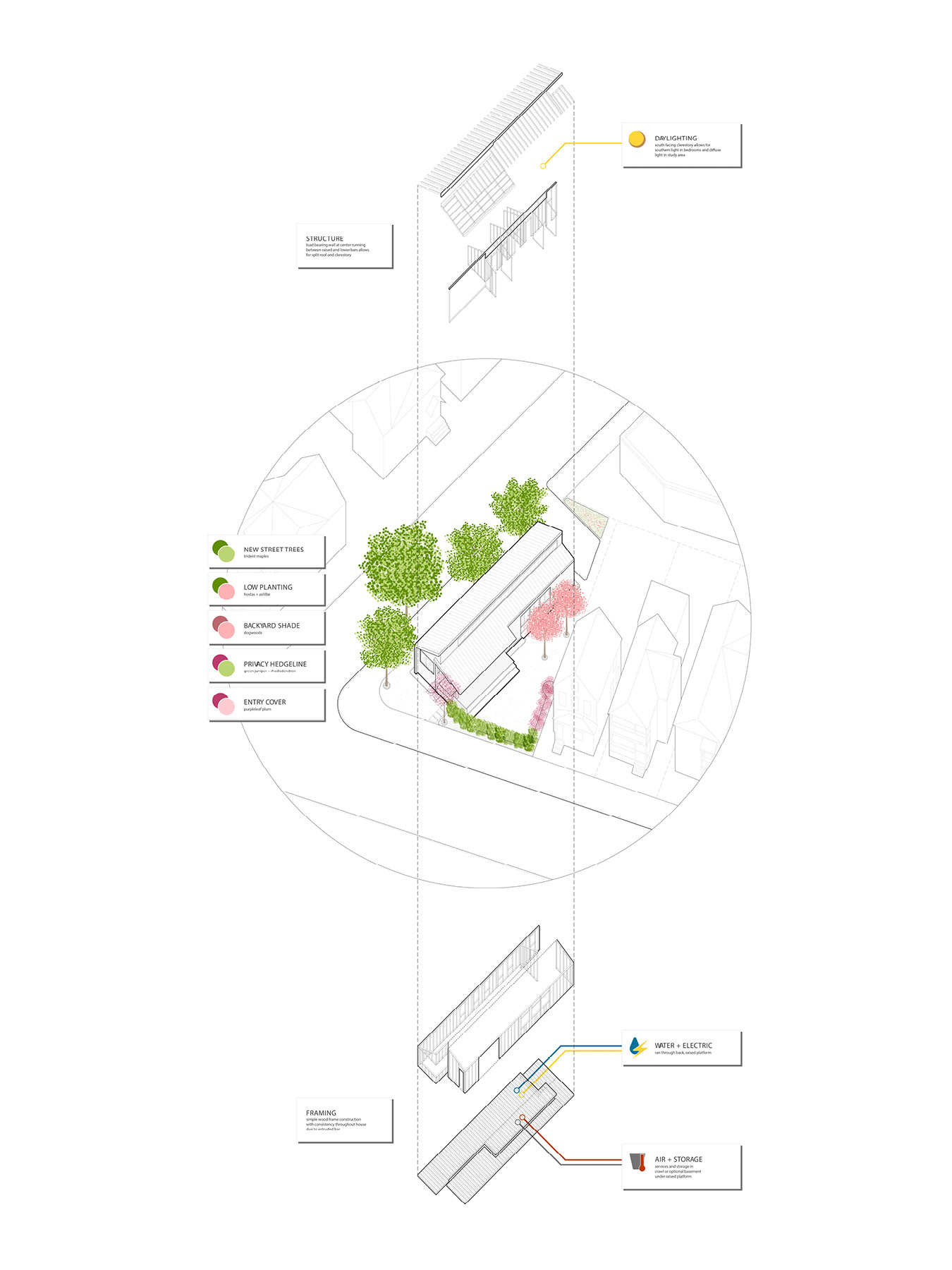

2015

This project was completed in collaboration with Anny Chang, Michael Loya, Cecily Ng, Maddy Sembler, and Wes Hiatt and with studio instructors Trattie Davies, Peter DeBretteville, Amy Lelyveld, Alan Organschi, Joeb Moore, and Adam Hopfner.

This project was completed in collaboration with Anny Chang, Michael Loya, Cecily Ng, Maddy Sembler, and Wes Hiatt and with studio instructors Trattie Davies, Peter DeBretteville, Amy Lelyveld, Alan Organschi, Joeb Moore, and Adam Hopfner.

Architecture

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

YALE BUILDING PROJECT

This house for a corner lot in New Haven, CT, is a long, one-story scheme in which two split bars shift in section. This shift allows the house to maintain some privacy from Scranton Street, to which the house aligns. The length and thinness of the scheme grants the most generous possible side yard and also serves as a garden wall, sheltering the yard from passersby.

The living room and kitchen are located in the front of the house and are connected to the porch and the widest portion of the yard. The rear half of the house contains more intimate spaces including bedrooms and an office/play room as well as a utility zone. A clerestory window that runs the length of the house brings in southern light.

The landscape ties outdoor zones into the patterns of scale, intimacy, and utility set out by the interior plan. The ease of constructability from the one bar scheme allows the house to be adapted and reproduced in several succinct solutions.

This house for a corner lot in New Haven, CT, is a long, one-story scheme in which two split bars shift in section. This shift allows the house to maintain some privacy from Scranton Street, to which the house aligns. The length and thinness of the scheme grants the most generous possible side yard and also serves as a garden wall, sheltering the yard from passersby.

The living room and kitchen are located in the front of the house and are connected to the porch and the widest portion of the yard. The rear half of the house contains more intimate spaces including bedrooms and an office/play room as well as a utility zone. A clerestory window that runs the length of the house brings in southern light.

The landscape ties outdoor zones into the patterns of scale, intimacy, and utility set out by the interior plan. The ease of constructability from the one bar scheme allows the house to be adapted and reproduced in several succinct solutions.

2014-2020

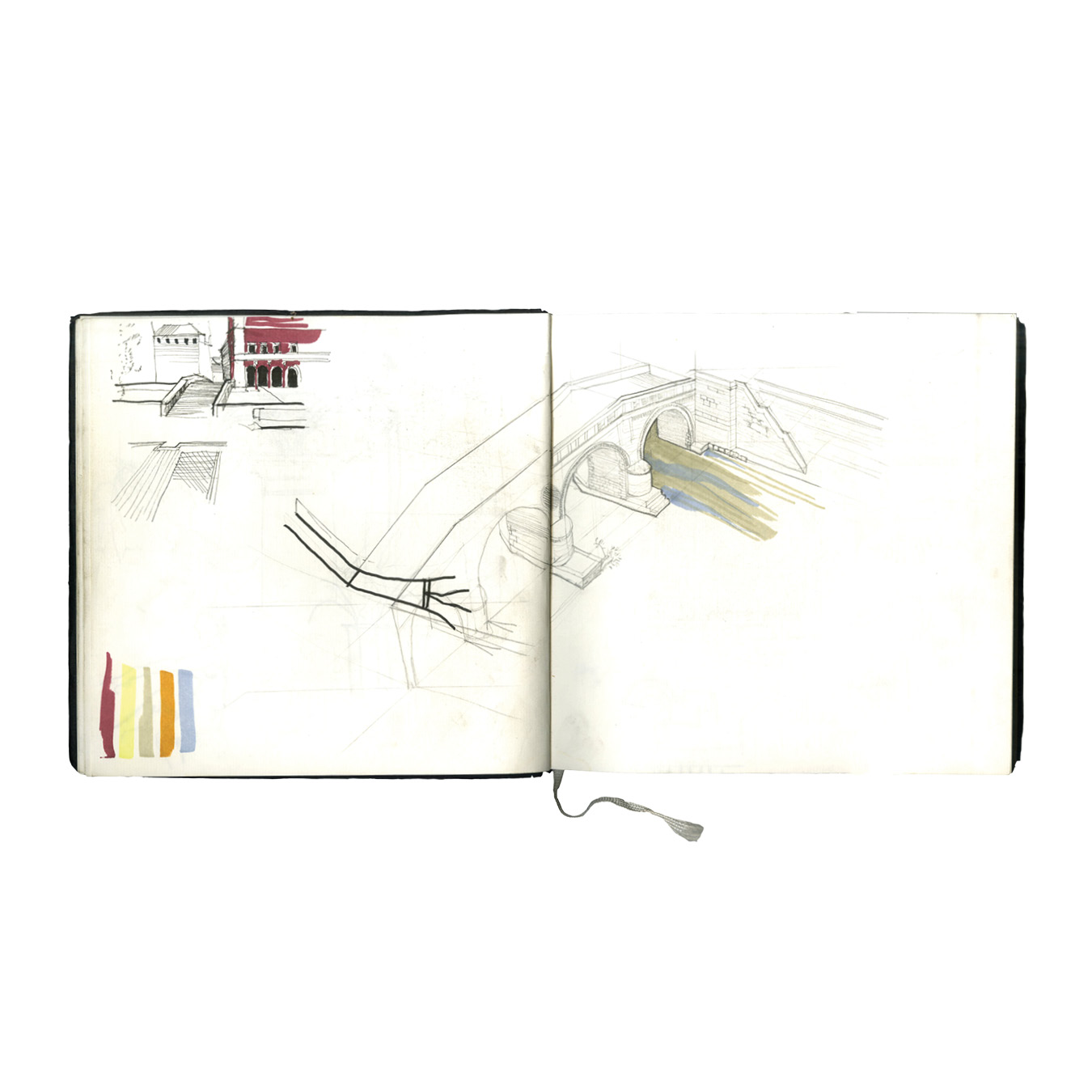

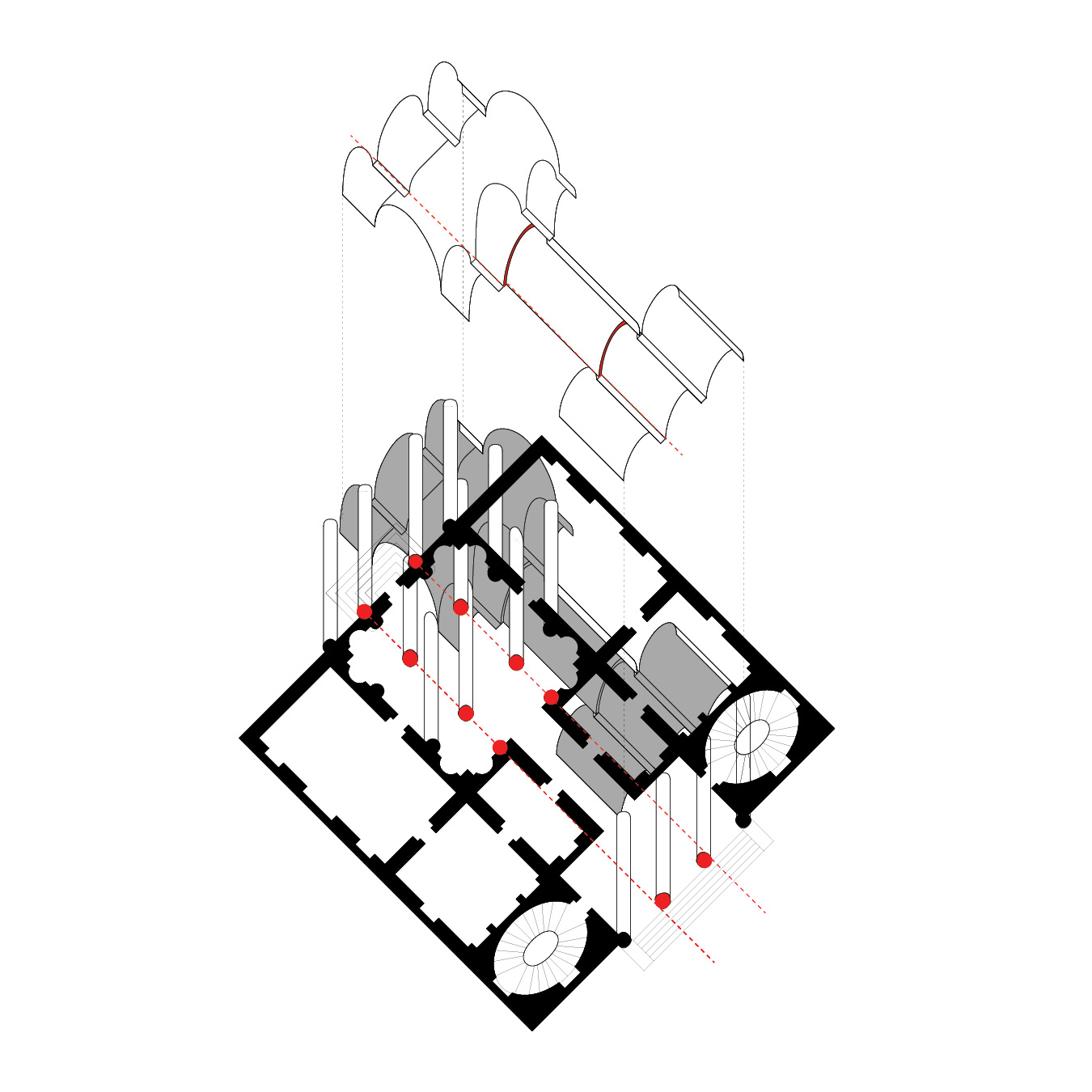

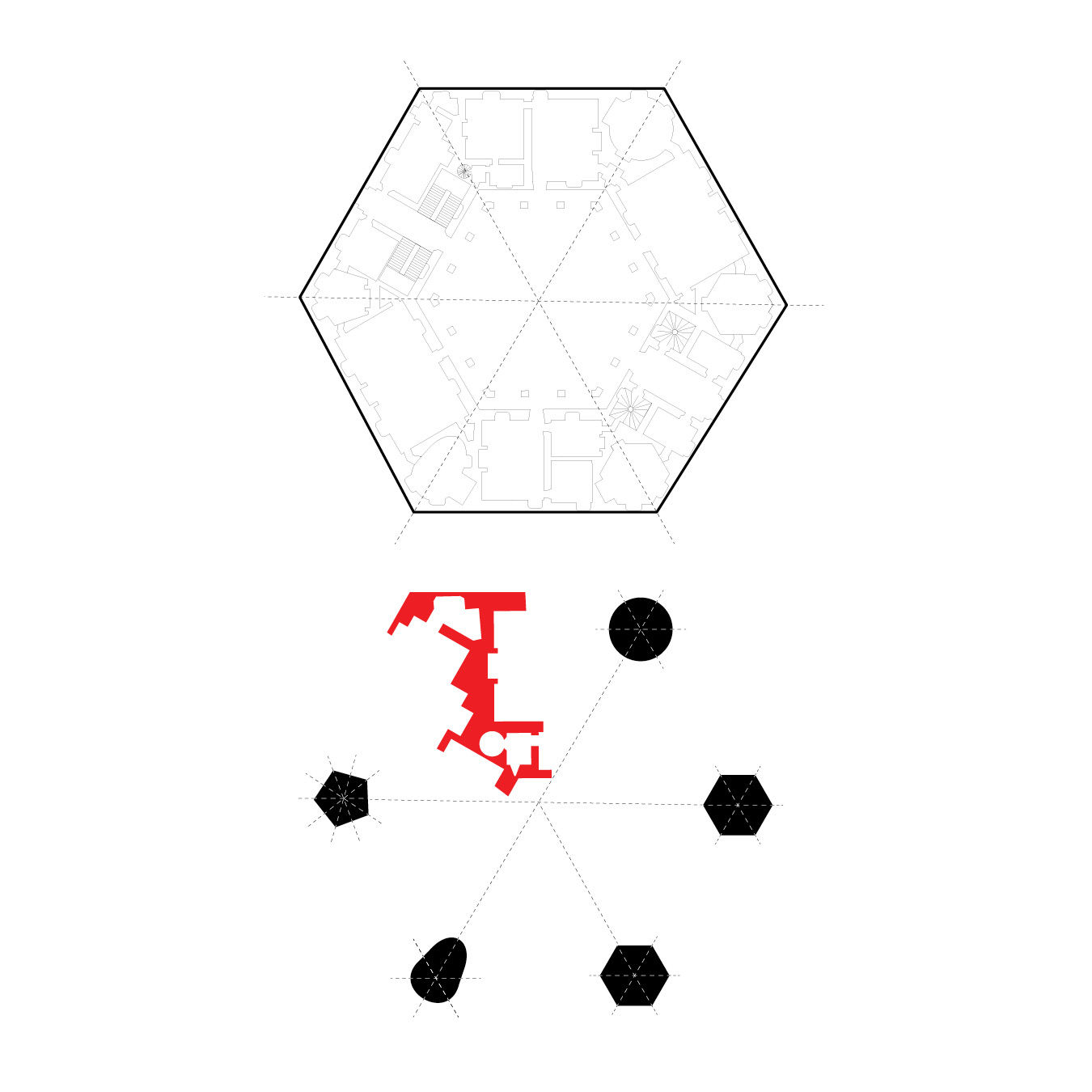

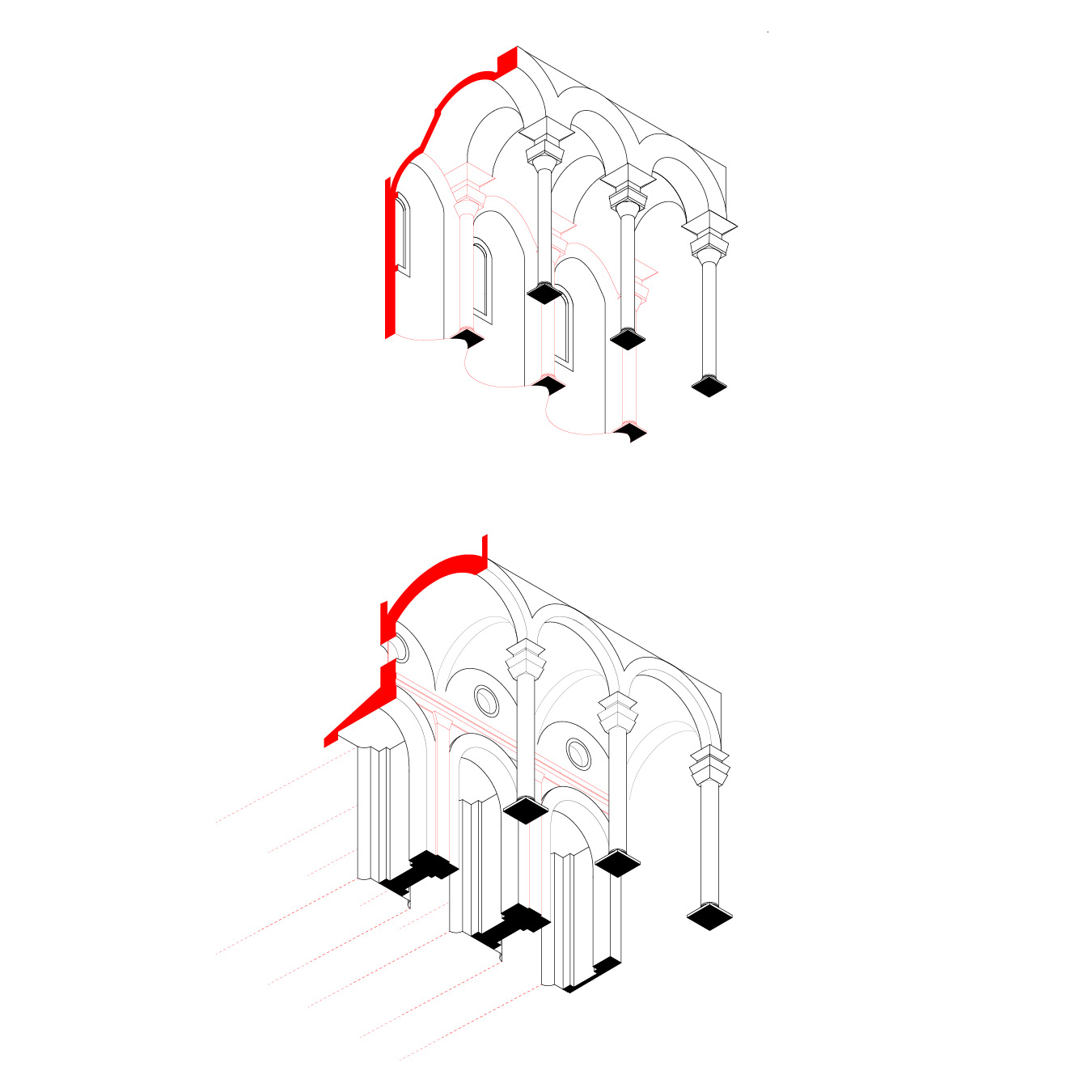

Drawings completed for courses at the Yale School of Architecture.

Drawings completed for courses at the Yale School of Architecture.

Drawing

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

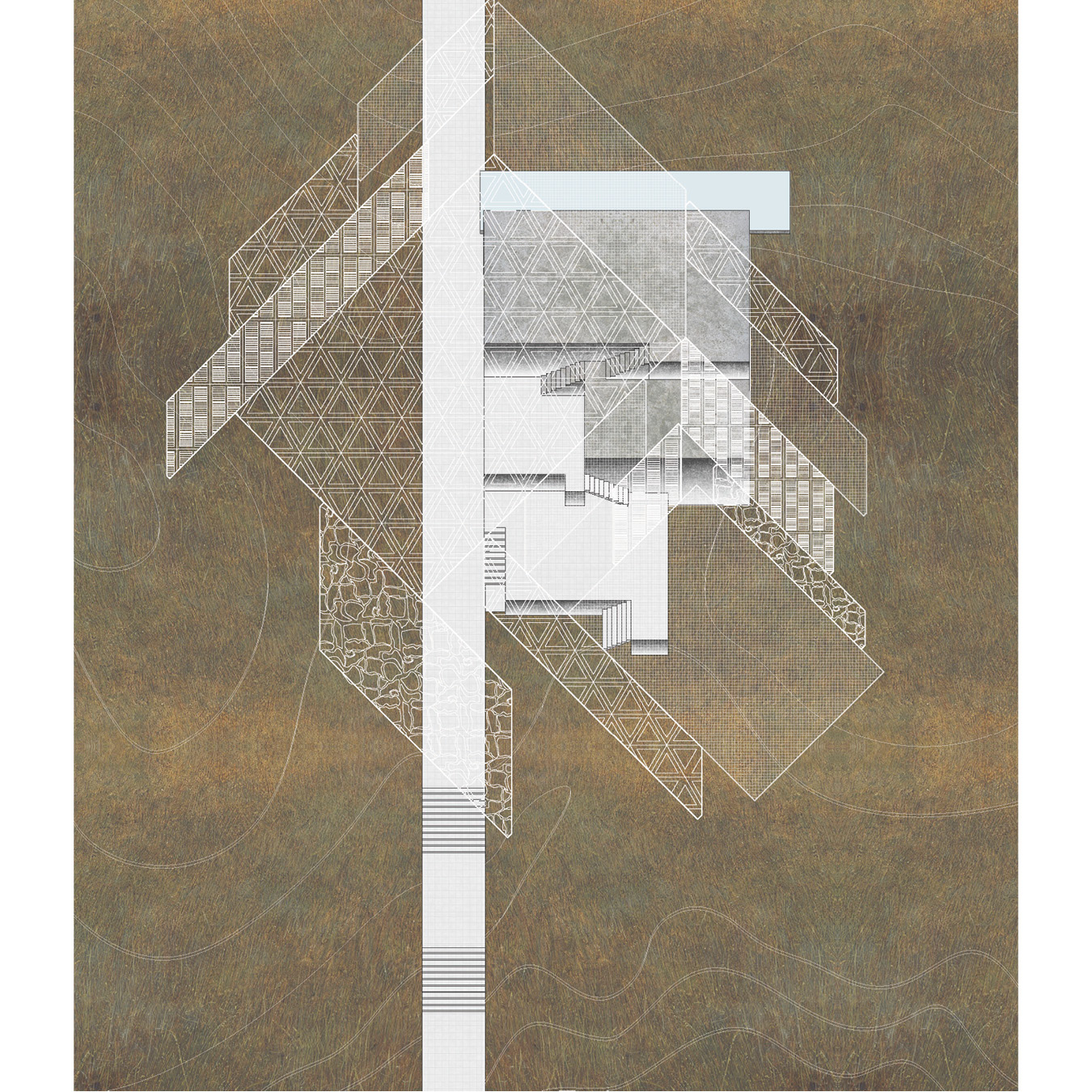

DRAWINGS

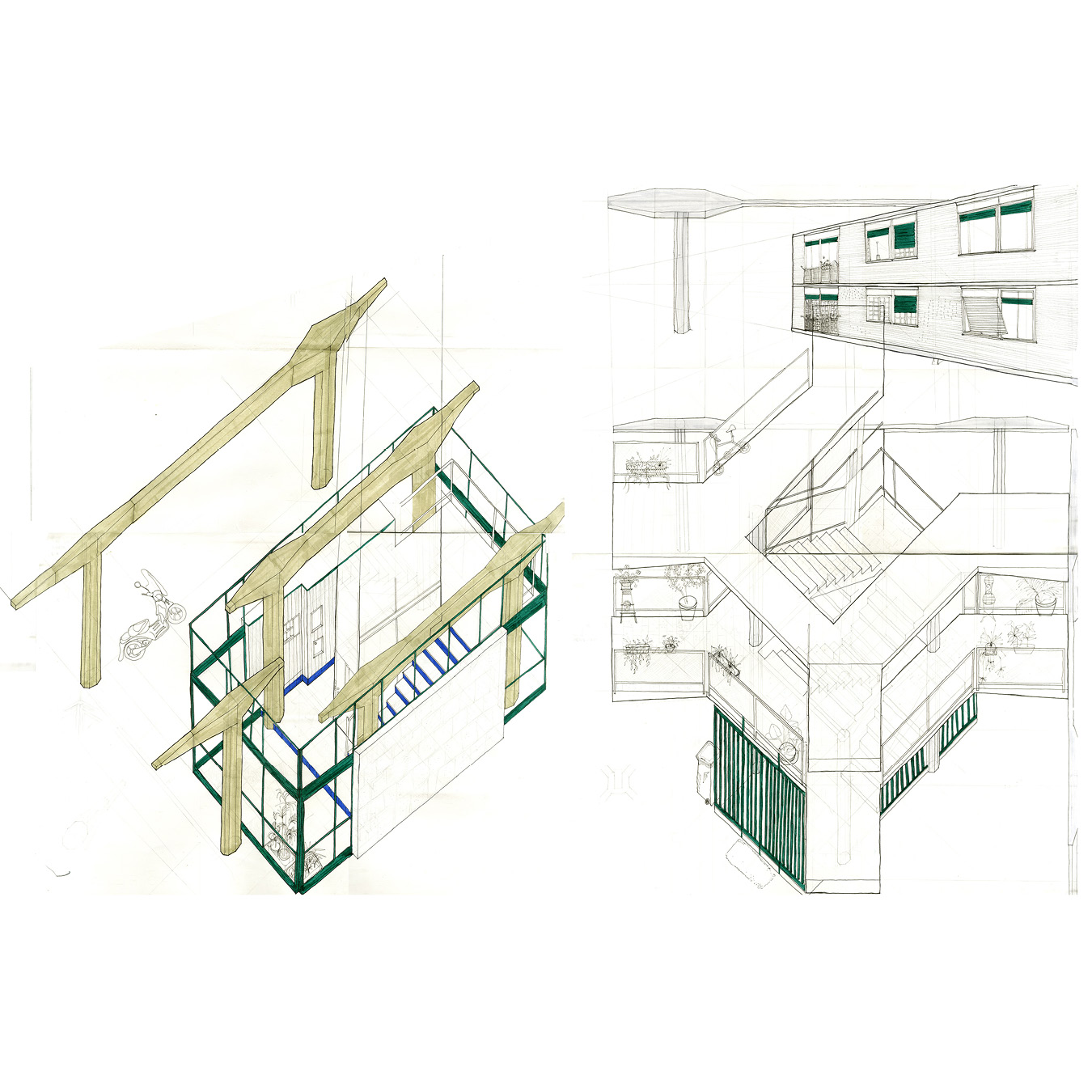

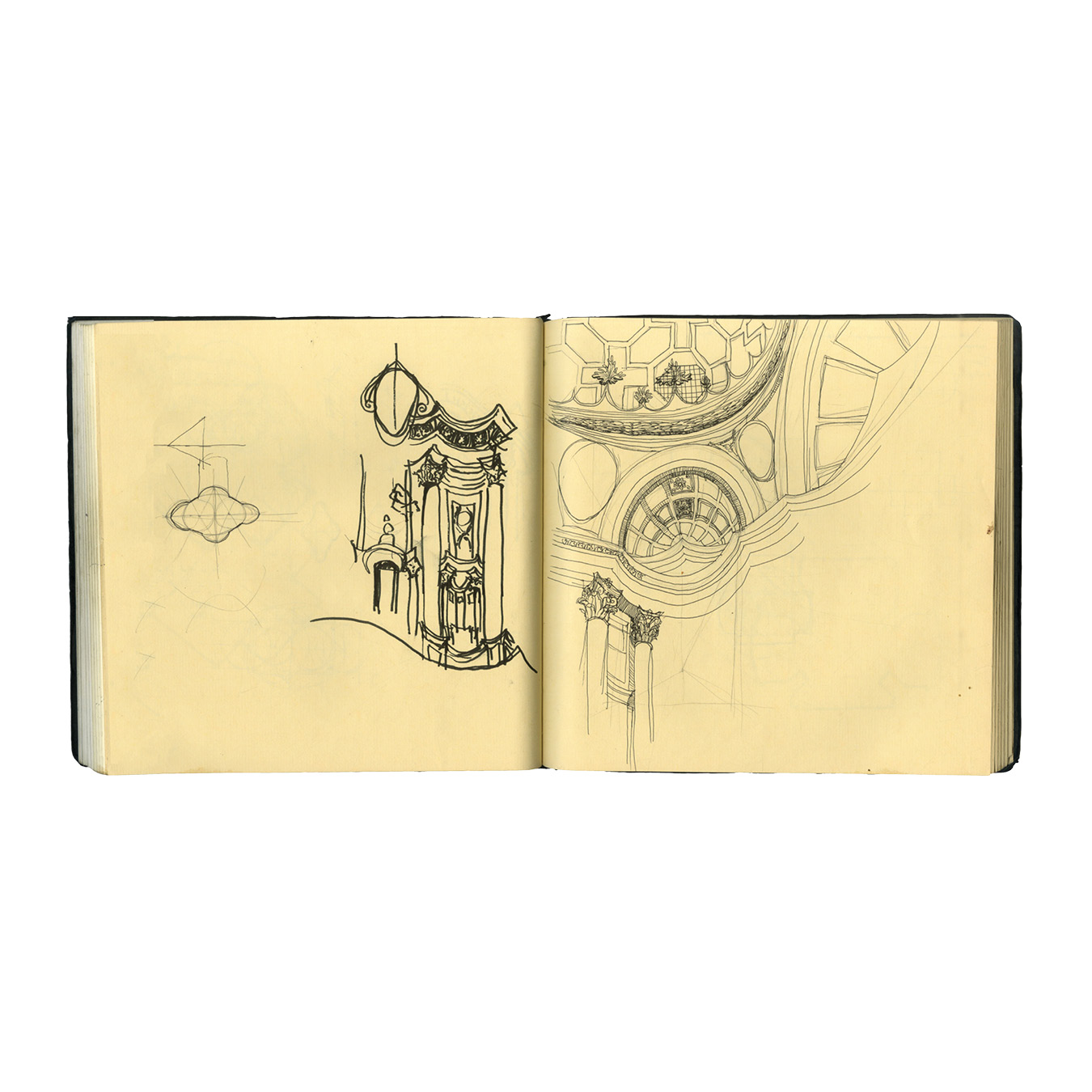

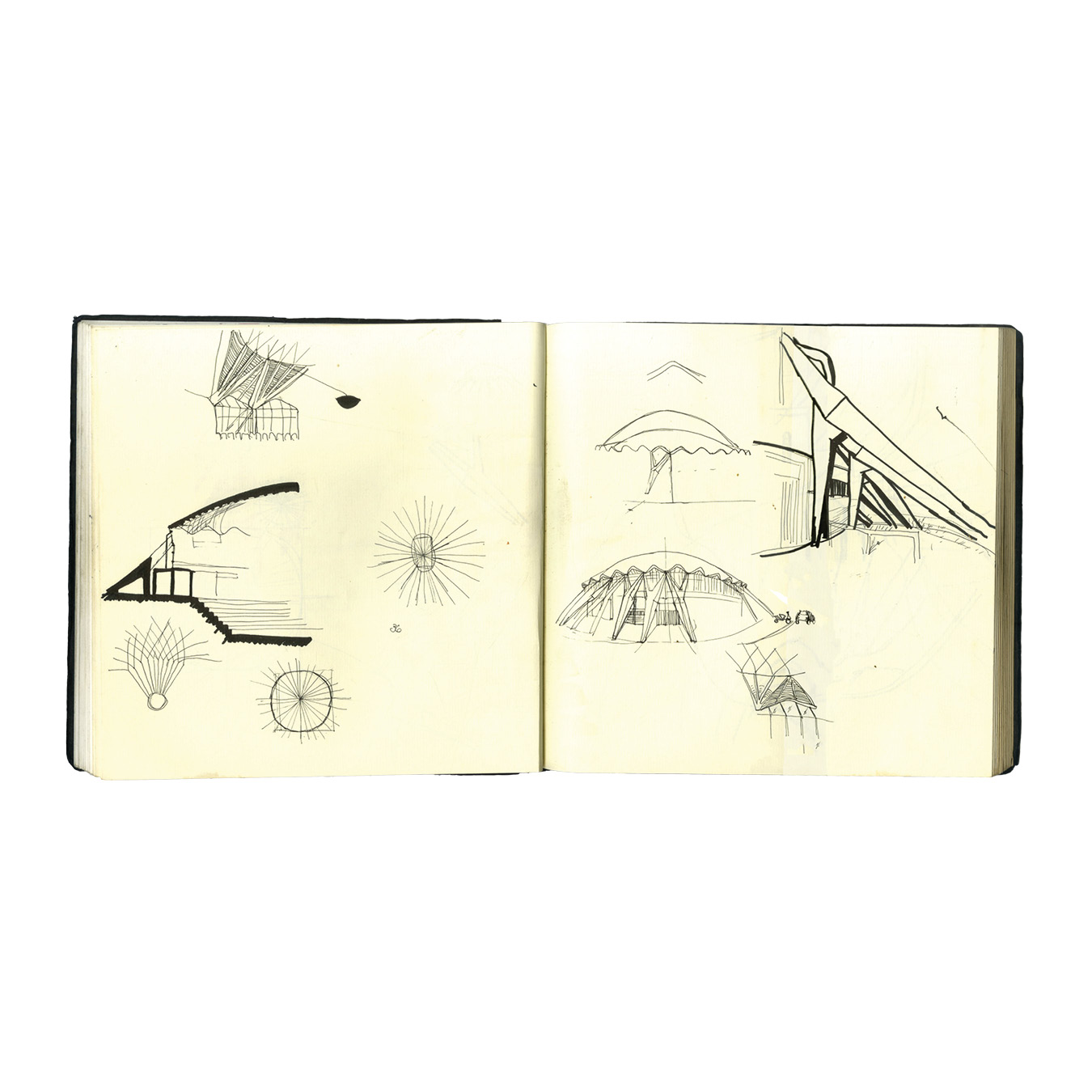

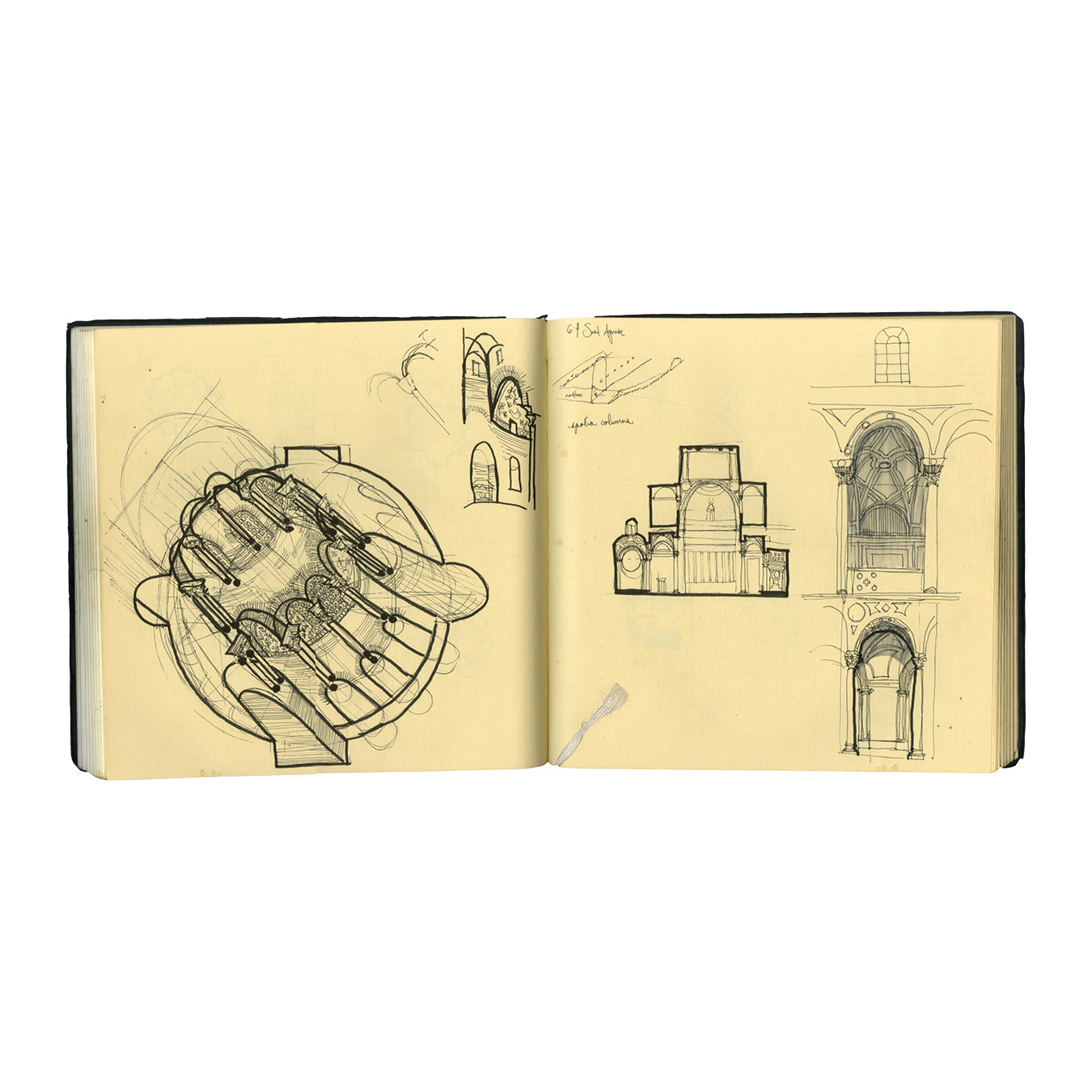

This set of drawings includes a selection of drawings done on-site in Rome, diagrams of works by Borromini, Palladio, Brunelleschi and Serlio, as well as illustrations of Shigeru Ban’s Villa Vista house in Sri Lanka.

This set of drawings includes a selection of drawings done on-site in Rome, diagrams of works by Borromini, Palladio, Brunelleschi and Serlio, as well as illustrations of Shigeru Ban’s Villa Vista house in Sri Lanka.